|

|

|

| |

"Often

one plans and builds something

that later shows itself to be less interesting or

of less value than originally anticipated.

Occasionally the reverse is true: the product

proves better than hoped for."

(John Allen, Model Railroader, November

1972)

|

| |

|

| |

My Z Scale layout is

entirely the result of "trial and

error" and a long journey of "back and

forth".

|

| |

|

|

Much

of what has materialized

in the end happened to do

so because my initial

idea didn't work at all

or simply because I

changed my mind.

At

times it was like seeing

only a hazy shade of a

distant train in the fog,

other times it felt like

pushing on with a fast

freight through a

snowstorm wipeout.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

But it all came

together in the end - the result of

"accidental modelling".

|

| |

| |

|

THE

LURE OF THE CONTINUOUS RUN

|

|

|

|

| |

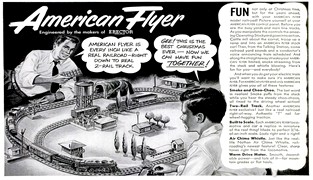

| Something

that separated real trains from model trains

since the latter's inception was the direction

their travels would take them in. In the real

world, trains would travel from A to B, whereas

model trains generally just ran around in

circles. |

| |

|

|

No

matter the scale, the brand or the style,

"starter sets" have come with

either a circle or an oval of track for

decades. As boys playing with toys

evolved into serious modellers, the

starter set's oval of track was

recognised as being very far removed from

actual train operations, subsequently

frowned upon, and finally given the

derogatory labels "toy set" or

"tail chaser".

|

|

| |

| In

an attempt to elevate it far above and

away from the toy train set, the term

"continuous running" was

coined, and serious modellers built some

serious layouts which strived to

camouflage as best as possible the fact

that trains ran in circles. The companies

making model train starter sets also

tried to improve the perception of the

basic oval, by adding double and triple

track running as well as more and more

complex yards and sidings - all provided

for, step by step, through

"expansion packs" of track to

this day. Individual railway

modellers came up with more prototypical

linear layouts very early on in the

hobby's history (such as A. R. Walkley in the mid-1920s or Cyril J. Freezer in the 1950s), but the

happy memory of watching trains pass by

(albeit in a repetitive circle) persisted

in many railway modellers.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The lure

of continuous running is

at least partly rooted in

its resemblance to what a

person standing trackside

in the real world sees: a

train approaches from one

side, runs by, and then

disappears to the other

side of the onlooker's

position. Even though it

happens over and over

again on an oval of

track, the passing train

essentially recreates

this scene. It also

allows for a very relaxed

experience - with the

controller set to a fixed

speed, the assembled

model train will simply

loop around the track

without any further

handling needed. However,

one of the major problems

with continuous run

layouts is the space

required to accomodate

them.

|

|

|

|

| |

| They

are space hungry because they have to

accomodate semi-circles of track; in the

most popular modelling scale of HO/OO,

even using the fairly tight so-called 2nd

radius curves requires a minimum board

width of at least 100cm (40 inches) -

although this will give very little room

outside the track for e.g. scenery, so

actually a baseboard width of 120cm (48

inches) is called for. Having

(too) many hobbies that all require space

has put me in a position of lacking an exclusively

designated, permanent "model railway

space" for most of the time. And

whilst this introduced me to "shelf layouts" and

"shunting puzzles", the lure

and pull of the continuous run layout

with its trainspotting perspective always

remained, and strongly so.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

Z SCALE: DESKTOP

RAILROADING

|

|

|

| |

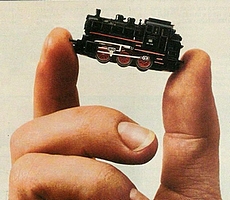

| Lack of space has always been one of the

main reasons for the development of smaller model

railway scales (such as the introduction of TT

(1:120/1:130) in 1945, and N (1:148/1:160) in

1962), but at a scale ratio of 1:220, Z Scale

offers the possibility of running trains in a

confined amount of space which simply would not

be possible in other modelling scales. |

| |

|

|

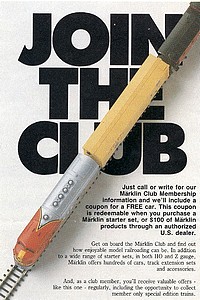

In

promoting Z Scale, Märklin

thus always emphasized

the smallness of the

models; besides choosing

the last letter of the

alphabet to designate the

scale, they also used the

moniker "mini-club".Initial

advertisements also made

certain to point out the

advantages in comparison

to the traditional space

(and skill) requirements

of larger modelling

scales.

"Nothing

like it has ever existed

before. Never before has

reality been presented in

such fascinatingly small

size and exciting detail

(...) Mini-club will

conjure up a wonder world

on your table, all in

full view, which you can

reach from your armchair.

No basement is required,

no suite of rooms and you

do not have to be a

do-it-yourself fan

either. The mini-club is

a true leisure time hit

and makes an exciting

hobby into a portable

leisure time game."

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

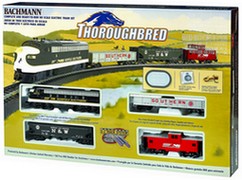

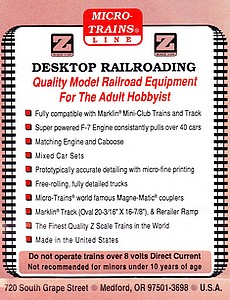

| Micro-Trains, on the

other hand, sold their US Z Scale train sets back

in the 1980s and 1990s as "desktop

railroading". Either way, modellers had

to be introduced to Z Scale, and starter sets for

continuous running on a circle of track were the

traditional and proven ticket. |

| |

Micro-Trains, 1992

|

|

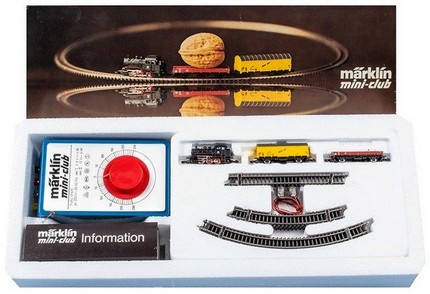

Märklin's

starter set with the diminutive

BR89 0-6-0 steam locomotive has

been on offer (with occasional

technical upgrades) since 1972

|

|

Märklin, 1986

|

|

|

| |

| The initial starter sets from Märklin

and Micro-Trains (containing Märklin track) came

with track ovals measuring only 51x44 cm (21x17

inches), and those small round-and-round layouts

became something of a calling card for Z Scale,

with some of them even finding sufficient space

within the confines of a briefcase. |

| |

|

|

As the years progressed, some of

Märklin's starter sets grew to to

include more track and turnouts (and in

some cases even two trains), but for

obvious reasons they always stuck with

the formula of the continuous run oval of

track.

I initially saw Z Scale

as nothing more than a gimmick; putting

together a briefcase layout seemed like the obvious

(and only) thing to do in order to see

the models run.

|

|

|

|

| |

| However,

once I actually got to run a few Märklin and

Micro-Trains models in the early 1990s, I started

to view Z Scale as a potentially serious

modelling scale. I was sold on desktop

railroading, but there had to be more to it than

just a simple circle of track. |

| |

| |

|

LOOP

TO LAYOUT TO NO LAYOUT

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| The

logical progression from the basic (starter pack)

loop of track is to build something a bit more

complex and interesting. Several "shake the

box" ready-to-run options are available,

ranging from Märklin's track extension packs to preformed scenicked layout

bases (some even contained in the (in)famous briefcase). They provide modellers with

layouts that could be compared to painting

pictures "by numbers": they are built

following reasonably straightforward

instructions, but the end result will be a layout

that is replicated by hundreds of other modellers

with very little room for individual touches. |

| |

|

|

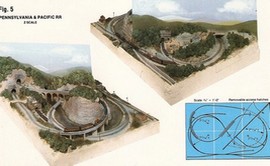

A

step up from this is to take some

inspiration from a trackplan someone else

has designed or even a layout someone

else has actually built. A very early Z

Scale example of the latter is the Pennsylvania

& Pacific, a layout that

featured prominently in the April 1985

issue of Model Railroader.

It was

accompanied by an in-depth portrait of (then still

fairly new) Z Scale and packed a lot of

model railroading and inspirational

allure into a mere 2'x3' (60x90cm). But

the transition from loop to layout can be

fraught with risks and tripwires.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Setting out to build a straightforward clone of the Pennsylvania &

Pacific with

regards to the track plan (a figure eigth folded

back onto itself), I decided to add my individual

touch to the layout by leaving out most of the

hidden track along with the scenic divider

running down the middle of the layout - which proved to be a huge

mistake. Whilst the layout was fun to build, simplifying the scenic contours

seriously diminished the visuals and resulted in

a somewhat disappointingly uninteresting layout. |

| |

| It was a classic

false start that completely derailed my

interest in Z Scale for a while. Linear

shelf-size layouts in N and eventually

HO/OO scale were fun to build and operate

- but they didn't offer the delights of

continuous running. I therefore dipped back

in and out of Z Scale once every few

years, but none of the approaches

(modular or small single baseboard

layouts) were able to rerail things. It

almost seemed like Z Scale just wasn't

right for me - until I came across David

K. Smith's James River Branch layout and website by chance in late 2011.

|

|

|

|

| |

| I

was completely mesmerized not only by his superb

modelling efforts but also by the approach (you

might even say philosophy) to modelling in Z

Scale that he formulated (which also happened to

include the assertion that false starts are, quite simply, part of the

modelling process). His layout was small and a

simple single track affair, measuring a mere

15"x36" (38x92 cm), but it was

massively inspirational. I also got almost

everything wrong about it all, and it sent me on

a decades-long back-and-forth journey from one

layout project to the next - none of which really

worked out. And it took me an embarrassingly long

time to realise why. |