|

| |

"The lure of the

full-size railway is what in the first place draws

many people to the model railway hobby. It is at this

intangible level of the emotions that the railway

makes its strongest appeal, although the

technological and historical aspects are undeniably

full of interest." (Terry Allen, Encyclopedia of Model

Railways, 1979)

There are many ways and many

channels through which the incentive spark for railway

modelling may catch on; here are some sources of

inspiration which had an impact on Pecan Street in

specific as well as on my railway modelling in general.

|

| |

|

| |

| Like

many others, I was introduced to the hobby as a

young child through an oval of track laid out on

the living room floor, and a train whizzing

around, backwards and forwards. Those trains were

either Tri-ang OO models based on British

prototypes or Lima HO continental European

models. And like

many others, my interest in model trains gave way

during my teenage years to other things. The

impetus to get back into the hobby as a twen was

in no small way triggered by a display of a few

HO American models in a local model shop's

window. Neither the locomotive type (GP40) nor

the railroad company (Cotton Belt) meant anything

to me at the time, but I liked the look and feel

of it enough to buy one - and get back into model

trains.

While the model shop has

been gone for a good thirty years now, I still

have that Atlas GP40. Back in 1984 the running qualities of

this flywheel equipped locomotive were head and

shoulders above the average European model

specifications, which was slightly ironic since

this GP40 was made for Atlas by Roco in Austria.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

MODEL

TRAINS WITH A PURPOSE

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Even when I got back into

the hobby, an oval of double track and a

few sidings seemed to be what model

trains were all about (albeit now run on

a sheet of plywood).

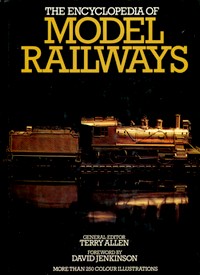

Terry Allen's Encyclopedia

of Model Railways (Octopus, 1979)

changed all that, by making me realize

that you could actually run model trains

with a purpose. It was the first time I

read about waybills and how North

American modellers ran freight trains in

a way that emulated the real thing. I

also discovered that an end-to-end layout

could be a consuming challenge if you

actually followed British railway

prototype practice. It was nothing short

of a revelation, and it totally changed

my perspective on railway modelling.

A

book was, of course, a typical

information channel of the 1980s and

early 1990s, before the advent of the

internet and social media. Today,

inspirational input on how to not just

model railways but do it in a way that

provides sustained entertainment can be

found in enormous numbers and in

generally high quality. Websites, online

videos, social media groups and many more

provide almost endless ideas and

encouragement, and no matter if you're a

beginner or a seasoned modeller, there's

bound to be something out there that will

kickstart your creative thoughts.

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

FROM

SMALL LAYOUTS TO MICRO LAYOUTS

|

|

|

| |

| One thing the "Encyclopedia

of Model Railways" didn't change was

the idea that you needed one of

those sprawling and grandiose

layouts the modelling press was (and often still

is) championing in order to have fun. It wasn't

until the arrival of the world wide web in the

early 1990s that I gradually discovered

alternatives in the form of small layouts focused

on operation: John Allen's Timesaver, Alan Wright's Inglenook Sidings, or Scot Osterweil's Highland Terminal. They all provided inspiring

templates and introduced me to the shelf-style

"small layout equals great fun"

formula. |

|

| |

|

|

But there was

something even smaller than small - the minimal

space "micro layout". Its champion

was Carl Arendt (1936-2011) who, having built his

first micro layout in 1966, launched a highly

influential website

in 2002 which ultimately became the definitive

take on tiny layouts.

"Micro

layouts are small model railroads, usually

less than three or four square feet in area,

that nonetheless have a clear purpose and

excellent operating capability."

(Carl Arendt)

Arendt (who also published three books on the

subject matter) passed away in 2011, but his

website continues

to be accessible.

|

|

| |

| Another highly

influential source of inspiration for small and

tiny layouts was Chris Ellis (1937-2025), who

self-published the bi-monthly Model Trains

International magazine from 1996 to 2015 for

a total of 118 issues. I would regularly browse

Carl Arendt's website and had a long-standing

subscription to MTI throughout the mid- to late

2000s, but for the longest time micro layouts

were more of an interesting curiosity to me than

a template which I would want to use for my

personal layout. As is so often the case, the

right circumstances had to emerge. When I replaced my 2004 Little

Bazeley 00 scale shunting puzzle in 2021 with its

Mk2 version, I remained without a

layout for my small collection of HO scale

US locos and freight cars. I was, it seems, in

layout planning and building mode, and found

myself contemplating the possibility of having a

second, American style switching layout.

|

|

|

|

| |

| But being, at least for the moment, without a

dedicated space to permanently set up a layout (let alone

two), a second layout would need to have a very small

footprint. And that's when I remembered a specific type

of micro layout. |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

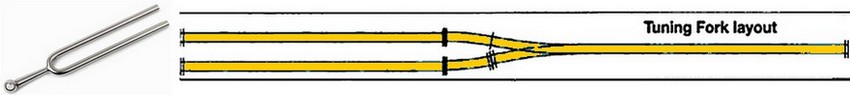

| Working within the micro layout framework, Chris

Ellis (himself a prolific designer, builder and operator

of such small layouts) first introduced what he called a

"tuning fork layout" as an "ultra

simple multi-mode switching plan" in Model

Trains International #45 in March 2003. |

| |

|

| |

The concept as such is much older, but Ellis

was the first to pin it down and give it a name

that stuck.

"A very

small layout indeed, not much more than a

diorama (...) just 4 ft long and 4.5 in.

wide; I call it the "Tuning Fork",

because that's what the track layout looks

like - a Hornby Y point in the middle giving

two parallel tracks or sidings (...) This

doesn't sound like much but in practice it is

immense fun, very quick and easy to set up,

totally portable, light and quick to

build." (Chris Ellis, The

Hornby Book of Model Railways, 2nd

edition, 2009)

|

|

| |

I was inclined to believe Ellis,

since another prolific author, Lane

Mindheim, arrived at the same conclusion

(and pretty much track layout), albeit

coming from a completely different angle

of approach (his "one turnout

layout" is

primarily rooted in the greatly

simplified track layouts of contemporary

US railroads). So whereas Ellis

saw the "tuning fork" as an

escape hatch for the space-starved

modeller, Mindheim

perceived a realistic track pattern for

prototypical operation in an achievable

format:

"A

layout that [...] is within the reach

of any hobbyist, is inexpensive, and

only has one turnout [...] can be

both highly plausible and fulfilling

to operate."

|

| |

|

|

Mindheim's

concept of how to design, build

and operate a realistic (modern)

switching layout is highlighted

in four books he published

between 2009 and 2011, but quite

unlike Ellis, he is rather

generous with the actual space

allocated (notwithstanding the

occasional reference to a

"tiny footprint").

Which makes sense, since

Mindheim's "one turnout

layout" is concerned with

maximising prototypically correct

operation, not minimising the

layout's size. I wasn't

therefore going to follow any of

Mindheim's layout ideas per

se, but combining his

operations-based approach (which

I tend to call "modern

minimalist") with

Ellis's space-saving concept

provided me with the inspiration

to incorporate a little bit of

both of these sets of modelling

ideas.

It also reminded me of the

late great John Allen, whose

advice was to "start

small and build well, plan for

operation and build with care,

and you will be amazed at how

much fun a small pike can

be".

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| Every modeller has their

prototype favourites. When it comes to North American

railroads, I find that I pretty much like any kind of

locomotives, old or modern. |

| |

| However,

when it comes to rolling stock, I have a real

soft spot for boxcars.

They are, as the Union Pacific

points out on its website, "one

of the most iconic pieces of railroad equipment

and certainly the most recognizable".

But there's more to

boxcars than just that.

Together with the paint

schemes used on locomotives, they are also the

single most colourful element of North American

railroading, even if they come in the classic

"boxcar bauxite/brown" (since these

days they are inevitably covered in graffiti).

Of course boxcars have been

pronounced by many to be on the way out, and

their numbers have certainly dwindled in the face

of intermodal traffic.

But boxcars are still around

(mostly within mixed freights, but on rarer

occasions you can also find modern power still

pulling an entire string of almost nothing but

boxcars), and some experts even see a future for

them.

In terms of modelling

inspiration, having a preference for boxcars is

of course a perfect fit with most switching

layouts, since these commonly use boxcars as a

major type of rolling stock - so a "tuning

fork" layout would provide me with the

perfect excuse to build up and run a nice

collection of boxcars.

|

|

North Carolina Transportation Museum, Spencer NC,

13 April 2022

Markham VA, 18 November 2019

(click image to view short video of a string of

boxcars)

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| Where do layouts get their names from? Usually there

is at least some degree of personal connection present in

choosing what you are going to call your creation. |

| |

|

|

So why Pecan Street? There

actually is a Pecan Street located in Abingdon

Va, and not only does it run up to a level

crossing, it also intersects with Railroad

Street. What more of a hint (or, in this case,

sign) do you need?

The name has a nice ring to it, and since

Abingdon Va is one of my favourite places in the

US (and still has Norfolk Southern trains running

through it), it sort of stuck with me right from

the planning stage.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

PROTOTYPE

REALITY CHECK SPARK

|

|

|

|

| |

| With inspirational sparks both decades old and

recently acquired, a vague idea slowly began to take

shape and started morphing into a project. Now I was

curious to see if there could also be a "prototype

spark" - what did railroad locations with just a

single turnout look like in the real world, and was there

enough visual and operational appeal? |

| |

| My first discovery really

shouldn't come as a surprise - railroads in the

United States aren't the only ones who

rationalised their operations and simplified

their track layouts over time. Colnbrook Rail

Terminal, located on the western edge of London,

England, receives jet fuel which is then

transported onwards to Heathrow Airport by

pipeline. It was originally part of a railway

line that closed in 1966, and the remnants of

that line now form the oil terminal.

It is evident at first glance that Colnbrook

is most one of the closest prototype example

along the lines of Chris Ellis's "tuning

fork" layout concept you'll find anywhere in

the real world. In this view, taken in May 2021,

Class 60 054 has cleared the switch after a

shunting move.

|

|

J. Foulger photo

(licensed for reuse under

the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0

Generic License)

|

| |

|

Green Mountain RR, GP9 #1850, Smithview VT, 1991

George Melvin photo, © Adrian Wymann collection

Springfield Terminal, SW9 #1424, Winslow Me, 1992

© Adrian Wymann collection

|

|

The prototype locations in the US

featuring a single switch and two tracks

illustrated here are but a sampling - there must

be thousands of them. Not all of them are

"true" tuning fork track layouts like

Colnbrook; often one of the tracks continues on

as a through line. However, these vignettes do

convey an idea of what a layout could look like

in terms of atmosphere. A bit of research into

this type of track configuration in the real

world quickly showed just how diverse the

settings can be, ranging from switching across a

street to just two tracks in what seems like the

middle of nowhere, surrounded by nothing but

trees - and pretty much all and anything in

between.

Boston & Maine, GP9 #1804, unknown location,

1983

© Adrian Wymann collection

|

|

| |

| Applying these findings to a

model layout with just one switch meant that

there was an enormous scope of different types of

settings and overall atmosphere to choose from -

yet another point very much in favour of the

simple "tuning fork" layout. |

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| I assume every modeller has them - one or (more

likely) more boxes full of kits and items that were

bought at a point in time in the past for a layout or a

module or a project that, at least so far, has not

materialized. |

| |

| In my case, I had a stack of

various items that had been aquired over time for

a US prototype switching layout based on an

industrial park. Plans had been drawn up, and

even a few tentative first steps undertaken, but

things never progressed too far because, quite

simply, I lacked the space I felt was needed.

Of course, it was very convenient to have all

those items stashed away and thus ready at hand

when the inspirational flash for Pecan Street

hit. But perhaps most importantly, putting

together this micro layout also meant that at

least some of those items stored "for

later" actually got put to use.

Using mostly what I already had then became a

major drive in making Pecan Street happen.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Text,

prototype and model pictures are (c) 2022-2025

Adrian Wymann.

|

| |

page created 11 March 2022

last updated 19 July 2025

|

|

| |