|

|

|

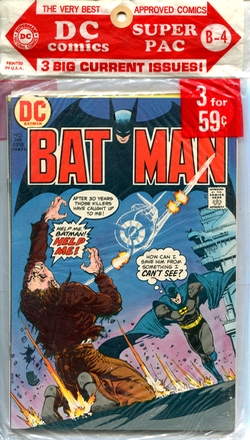

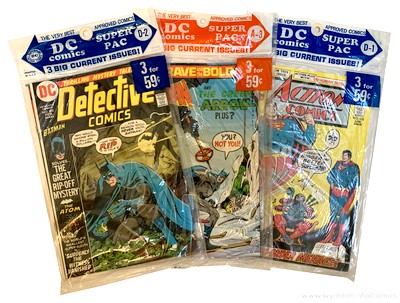

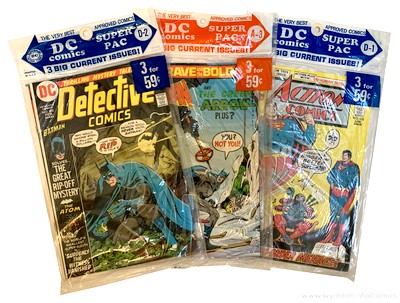

BATMAN,

LEGION OF SUPER-HEROES &

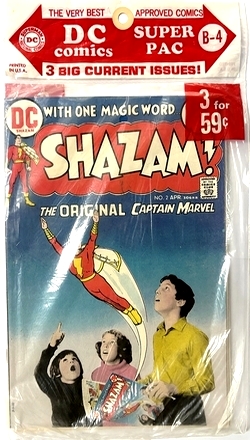

SHAZAM

BACK

TO BACK IN THE

APRIL

1973 B-4 DC SUPER PAC

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| In spite of

the hugely successful comeback of the superhero genre in

the early 1960s, the comic book industry had a problem:

its traditional sales points were fading away. Small

stores that had carried comic books were pushed out of

business by larger stores and supermarkets, and

newsagents started to view the low cover prices and therefore

tiny profit margins comics

had to offer as a

nuisance. Comic book

publishers desperately needed to open up new sales

opportunities and and tap into a new customer base. One

place these potential buyers could be found were

supermarkets, chain stores and gas stations - but in

order to be able to sell comic books at these locations,

the product would have to be adjusted. |

| |

| Handling

individual issues clearly was no option for these

outlets, but by looking at their logistics and

display characteristics, DC Comics (who came up

with the Comicpac concept in 1961) found

that the answer to breaking into this promising

new market was to simply package several comic

books together in a transparent plastic bag. This

resulted in a higher price per unit on sale,

which made the whole business of stocking them

much more worthwhile for the seller. The simple

packaging was also rather nifty because it

clearly showed the items were new and untouched,

while at the same time blending in with most

other goods sold at supermarkets which were also

conveniently packaged.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Supermarkets were even supplied

with dedicated Comicpac racks, which enhanced

the product appeal even more since the bags containing

the comic books could be displayed on rack hooks in an

orderly and neat fashion. It almost

became an entirely different class of commodity,

and offered parents (and their kids) the opportunity and convenience to pick

up a few comics at the same time they were doing their

general shopping. |

|

|

"DC's focus

[for the Comicpac] was on both the

casual reader and the parents and

grandparents who were looking for

gifts." (Wells, 2012)

DC's

"comicpacks" were a success,

and other publishers quickly started to

copy the concept.

"The

DC [comic packs] program lasted well

over a decade, with pretty high

distribution numbers. The Western

program was enormous - even well into

the '70s they were taking very large

numbers of DC titles for distribution

(I recall 50,000+ copies

offhand)." (Paul Levitz, in

Evanier 2007)

By the early

1970s, DC relaunched their comic packs,

calling them DC Super Pacs, and

they continued to sell well, containing

regular news stand editions.

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| This April 1973 (B-4) DC SUPER PAC contains Batman #248,

Legion Of Super-Heroes #3, and Shazam #2.

DC handled its multi-comic packs in

a very structured and organised manner; a B-4 pack from a

specific year would carry the same titles and issues no

matter where or when it was sold (rare packaging errors

aside). The digits (1-12) referred to the month and the

letters (A through D) marked the four different packs per

month. "B-4" therefore denotes the second April

SUPER PAC, in this case from 1973, containing comic books

with an April cover date (or April/May in the case of a

bi-monthly title). |

| |

| No

titles had permanent slots in the SUPER PACS, although

there was a high level of consistency with DC's flagship

characters (the SUPER PACs of 1973 contained complete runs

of Superman and Batman as well as the

Batman team-up title Brave and the Bold). But since sales points could vary a

lot with regard to their supplies and selection of SUPER

PACs, the availability of specific titles was never

guaranteed - something many

comic book readers in the 1970s had to put up with,

whether their comic books came packaged in a plastic bag

or as single issues from a display or spinner rack. But

since DC's editorial at large still very much embraced

the "single issue, done in one" storyline

principle during the early 1970s (rather unlike their

major competitor Marvel), it often didn't even matter in

which sequence you read your copies of Batman or

Superman. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

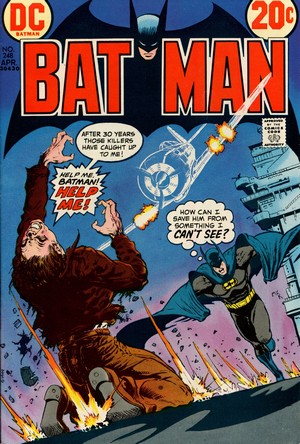

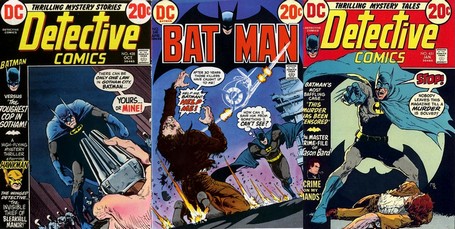

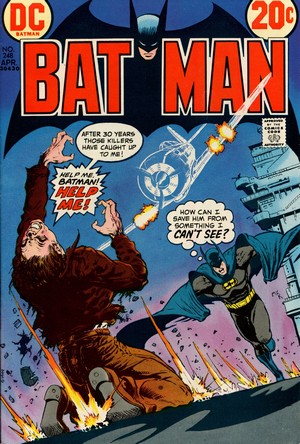

BATMAN

#248

April 1973

(monthly,

with the exception of Jan., March,

July and Nov.)

On Sale: 13 February 1973

Editor

- Julius Schwartz

Cover - Michael W. Kaluta (pencils &

inks)

Batman: "Death-Knell

for a Traitor!"

(13.5 pages)

Story -

Denny O'Neil

Pencils - Bob Brown

Inks - Dick Giordano

Lettering -

Ben Oda

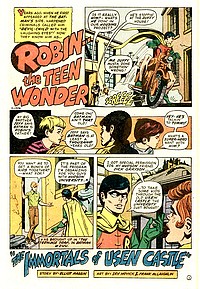

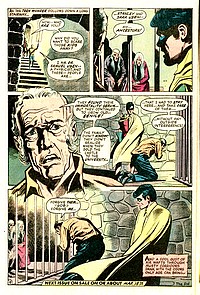

Robin: "The Immortals

of Usen Castle"

(9 pages)

Story -

Elliott Maggin

Pencils - Irv Novick

Inks - Frank McLaughlin

Lettering -

Milt Snappin

|

|

|

| |

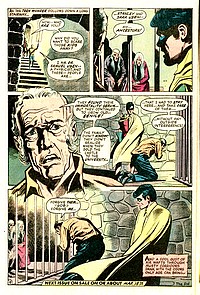

PLOT SUMMARY - Batman

tracks down an ex-Navy man who turned traitor during

World War II for a fabulous diamond; in the end the

traitor falls to his death after reliving the memory of

his ship being attacked by Japanese planes, and the

diamond is lost in the depths of the ocean. Dick Grayson

and Diane Lewis are giving some local youths a tour of a

castle that is supposedly haunted, but when Diana and

some of the children disappear, Dick changes to Robin and

discovers the secret behind the "ghosts" in the

castle.

|

| |

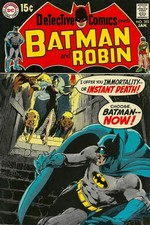

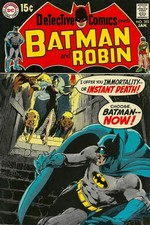

| Over the course of his long

publication history, the Batman has seen many changes

brought to his persona and his adventures. Some took

place gradually, others can be pinpointed to specific

issues - such as Detective Comics #395 (cover

dated January 1970, on sale 22 November 1969). Written by

Dennis O'Neil and drawn by Neal Adams and now a classic

in itself (reprinted in 2000 as one of DC's

"Millennium Editions"), it is often considered

to be Batman’s turning point as the Silver Age crossed

into the Bronze Age and the Darknight Detective returned

to his gothic roots. |

| |

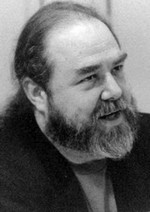

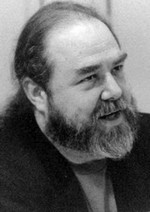

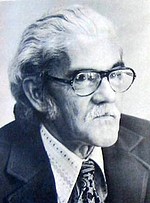

Dennis

"Denny" O'Neil

(1939 - 2020)

|

|

Other writers and artists were

also taking Batman down that path at the time,

but it was O'Neil's compelling concept that hit

home with readers and Batman editor Julie

Schwartz alike, and over the next few years, the

best was yet to come - not the least because

O'Neil had a clear-cut plan.

"The comics

at the time had been trying to follow the

example of the Adam West comedic TV show, and

they weren’t doing a very good job of it

(...) The books were being a bit shaky

sales-wise, as hard as that is to believe,

and Julie [Schwartz] wanted to continue to

publish Batman. So he came to me and asked,

“What have you got my boy?” What I

thought I had, and what I told people I had,

was that we were going back to what Bill

Finger started with in 1939, and we added to

that what the world had learned about telling

stories since then." (O'Neil, in

Handziuk 2019)

|

|

Detective

Comics #395

(January 1970)

|

|

O'Neil was very

methodical about his take on turning the Batman

into a much grimmer, darker

character.

"I went to

the DC library and read some of the early

stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane

and Finger were after." (O'Neil, in

Pearson & Uricchio 1991)

Ultimately,

this also resulted in underscoring the

investigative side of the Batman's persona -

effectively creating the Darknight Detective.

"There was

very little consistency. Sometimes he was a

detective, sometimes he was more a superhero.

When I took over the franchise I said okay,

this is the way we do it. Batman comics will

be about superhero stuff with a lot of

action, and Detective Comics is about the

same character functioning as a

detective." (O'Neil, in Handziuk

2019)

As a result, Batman and

Detective Comics took two entirely

different routes: whereas the latter title now

only featured plain clothes thugs and evil-doers,

Batman retained the costumed villains.

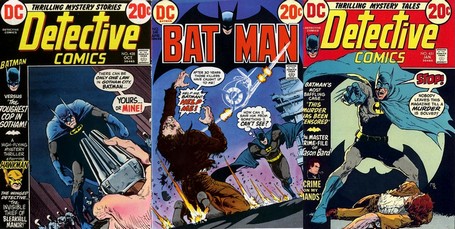

One significant and very noticeable aspect both

titles did share was a string of eye-catching

(and sometimes outright iconic) covers.

"The Batman

covers, whether they were [by Neal Adams] or

the odd ones that Mike Kaluta did during that

period, were set-pieces way above, I think,

most of the rest." (Levitz, in

O'Neil, Adams, Levitz & Evanier 2011)

|

|

Michael W. Kaluta (*1947)

|

|

Michael

William Kaluta (sometimes credited as

Mike Kaluta or MW Kaluta) pencilled and

inked three Batman and eight Detective

Comics covers between 1972 and 1974,

all of which convey a unique feel for the

iconic qualities of Gotham's Caped

Crusader. His cover for Batman

#248 (his first being for issue #242 and

his third and last for issue #253) is a

prime example of his ability to evoke and

capture the atmosphere surrounding the

Batman. |

|

|

|

|

| |

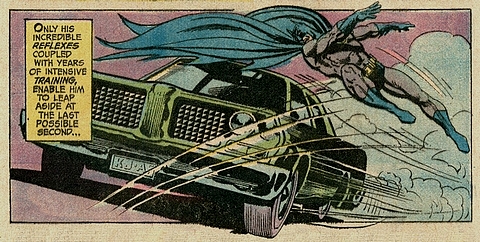

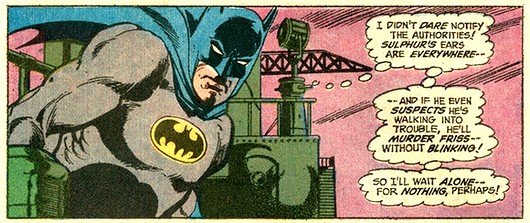

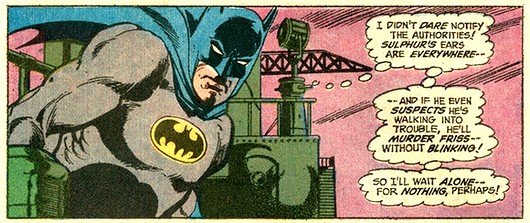

| The story told by Denny O'Neil in Batman

#248 - a "done in one" adventure that starts

and concludes in the same issue, as per the standard

formula still favoured by DC at the time - features

Colonel Sulphur as the costumed villain (after first

appearing in Batman #241). A decidedly

derivative "international criminal" (this would

be the last readers would see of him until he would

resurface for four brief stints in World's Finest

and Brave and the Bold in the early 1980s), he

is essentially watching from the sidelines as Batman

trails a former WW2 traitor in cahoots with the Colonel.

The plot has a few interesting psychological themes, but

it's thanks to the artwork of Bob Brown that Batman

#248 comes off as a marvelous piece of early 1970s Batman

lore. |

| |

| Brown started his career in comic books

in the 1940s, and did regular work for DC and

Marvel in the early and mid-1970s, including

almost 40 issues of Batman in Detective

Comics between 1968 and 1973 - but only this

one issue of Batman. Like many

other veteran contributors at DC Comics in the

early 1970s, Brown increasingly found his work to

be labelled as "old-fashioned"

(Evanier, 2004) - but his artwork for Batman #248 clearly

shows otherwise.

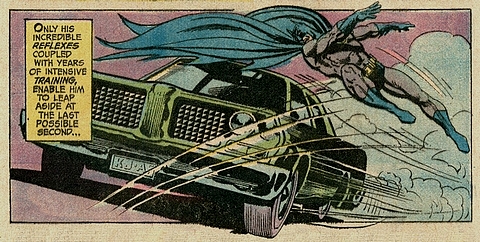

Throughout

this issue Brown's images have a wonderfully

dynamic flow to them (that car trying to hit the

Batman is leaving the panel boundaries and coming

straight at you), but his "silent" page

7 is a masterpiece. Very conservative in its

panel composition, the visuals are not only

stunning and telling the story without the need

for words but also feature (Neal Adams inspired)

iconic Batman vignettes. It just doesn't get any

better - and yet neither Batman #248

specifically nor Bob Brown in general have left

much of a mark in Batman's publication history.

|

|

|

|

| |

Bob Brown

(1915-1977)

|

|

Later in 1973,

Brown left DC for Marvel, and

that was that. He died four years

later from leukemia. Few Batman aficionados

will be able to tell you that

(together with writer Deny

O'Neil) he created the Caped

Crusader's first encounter with

the League of Assassins (Detective

Comics #405, November 1970) and

co-created the character Talia,

the daughter of Ra's al Ghul and

subsequently a recurring romantic

interest for Batman (Detective

Comics #411, May 1971).

"lt’s

somewhat unfortunate that

Adams’ undeniably dynamic

work on Batman towers over

his Bat-contemporaries.

Fortunately, Irv Novick, Jim

Aparo, and Frank Robbins (as

artist) have garnered due

recognition over the years.

Not so with Brown, however,

which is a shame, because his

pencil work on [Batman #248],

inked by Dick Giordano, is

outstanding."

(Kingman, 2011)

|

|

|

|

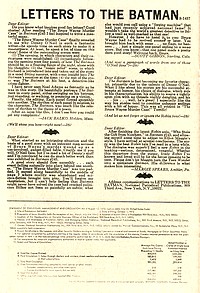

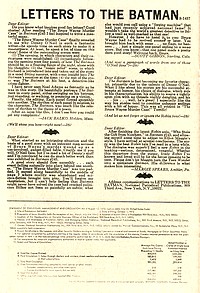

| Batman

#248 only contains a cut-down

letters page, due to the fact that one

third of the page is taken up by the

"Statement of ownership, management

and circulation". The postal services

had required a published statement of

ownership since the 19th

Century from all publications that were

shipped Second Class, but as of 1960

publishers were also required to list

their average circulation for the year.

Most readers at the time gave these

numbers only a cursory glance (if at

all), but today they allow us an easy

glimpse into print runs and sales of that

era.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| As far as Batman was

concerned, the numbers were down compared with the

average of the preceding 12 months: 404,000 copies

printed (compared to the average 478,125), of which

185,283 copies in paid circulation (244,488). However,

sales figures of Batman would recover and

increase for 1973 and 1974, before going on a sliding

trajectory which saw the number of issues sold on average

dip below 100,000 in 1983/84. |

| |

|

|

As was

typical for the early 1970s, the

attrition rate in terms of distributed

but unsold copies was terrible: totals of

201,414 (nearest to the filing date) or

185,283 (average of the preceding 12

months) meant that practically half of

the print run never made DC any money -

and the same applied to comic book

publishers across the board. The problem was

caused by the traditional distribution

model with returnability - which

essentially meant that the loss incurred

by unsold copies was on the publishers,

not the distributors or sales points. Not

surprisingly, it was a breeding ground

for an attitude of "we couldn't care

less" when it came to actually

selling the product.

"A

few retailers actually liked carrying

comics, but most were indifferent

(...) So, let’s say [the local

distributor] actually delivered 5,000

copies [of 10,000 received at the

warehouse] to the retailers - if they

bothered to deal with unwrapping and

sorting, if they had room on the

trucks… Most likely, they’d only

actually deliver comics to retailers

who would complain if they didn’t

get comics and places that sold

enough comics to make the driver’s

effort worthwhile."

(Shooter, 2011)

|

|

|

| |

Another huge problem were the

fraudulent practices it attracted.

"We [at Marvel]

actually found a company that was sending back more

copies than we shipped them. We found out there was a

printer in Upstate New York that was printing copies

of our covers to sell back to us (...) At the time we

had something like a 70 percent return rate"

(Galton in Foerster, 2010)

It all became completely untenable

by the time the 1970s rolled around and triggered the

impetus for the creation of "comic packs" such

as DC's Super Pacs and the direct market.

|

| |

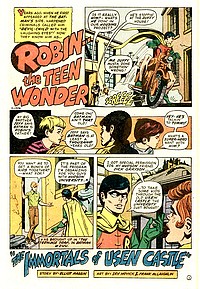

| As the 1970s rolled

around, Batman would either

feature a 20+ pages single or two shorter

stories involving the Caped Crusader,

before the second story slot began

featuring Robin as of Batman

#227 (December 1970). As of issue #230

(March 1971) the cover logo even featured

Robin's name before reverting back to

the long-established logo as of Batman

#241 (May 1972), but still featuring

Robin ("the Teen Wonder") as

backup (with the odd exception for an

issue or two publishing a longer Batman

story). This

arrangement would last until Batman

switched to DC's "pages Super

Spectacular" format as of issue #254

(January/February 1974), which then

featured multiple reprints including

Robin "the Boy Wonder"

(incidentally, that format also precluded

Batman being included in any

Super-Pac from January 1974 to March

1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Elliott Maggin

(*1950)

Irv Novick

(1916-2004)

|

|

The Robin back-up

story featured in Batman

#248 was the third of only seven

scripts penned by Elliott S.

Maggin featuring the Teenage

Wonder (appearing in Batman

#244, #245, #248-250, #252 and

#254). Known primarily for his

work on Superman, his Robin plots

feature interesting twists and

involve deep and far-reaching

topics - such as, in the case of

"The

Immortals of Usen Castle",

that immortality may come at the

price of suffering from eternal

old age and growing dementia. In

that respect, Maggin was often

somewhat ahead of his time when

it came to subject matters

infused into comic book stories.

| |

|

|

| Paired

with Maggin for the

artwork was classic

Bronze Age artist Irv

Novick (inked by Frank

McLaughlin), delivering

his reliably dynamic

pencils - and another

(almost)

"silent" page,

with plenty of action

over a total of six

panels but only one

speech balloon, one

thought balloon, and two

"sound

effects"...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

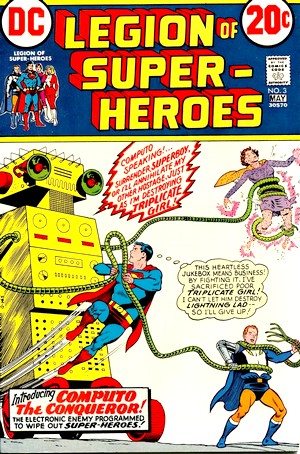

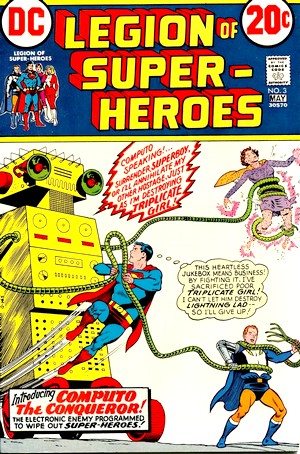

LEGION OF

SUPER-HEROES #3

April/May

1973

(bi-monthly)

On Sale: 13 February 1973

Editor - Jeff

Rovin

Cover - Curt Swan (pencils) &

George Klein (inks)

LEGION

OF SUPER-HEROES: "Computo

the Conqueror!" (16

pages)

Story

- Jerry Siegel

Pencils - Curt Swan

Inks - George Klein

reprinted

from Adventure

Comics #340 (January 1966)

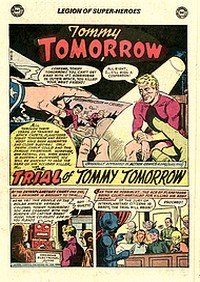

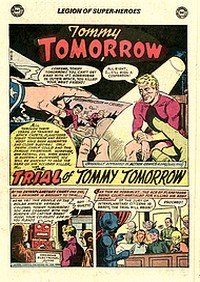

TOMMY

TOMORROW:

"The Trial of Tommy

Tomorrow" (6

pages)

Story

- Otto Binder

Pencils & Inks - Jim Mooney

reprinted from Action

Comics #240 (May 1958)

PLOT

SUMMARIES

- Brainiac 5's latest creation

turns on its master and the rest

of the Legion; Tommy Tomorrow is

put on trial for murder.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Comic book sales had been in a

steady decline since the 1950s (when top-selling issues

still enjoyed print runs of around or above 1 million

copies), but by the time the 1970s rolled around the

dropping sales figures meant that the only way to make

more money was to make sure you got a bigger slice of the

(shrinking) market - and one way to achieve that was to

put out more titles. And since the space at the sales

point was not going to increase, you could at the same

time push the competition off the shelves. Marvel was

the comic book industry's number one, but until mid-1972

DC still published more titles - until Marvel launched

the "war of the shelves" through a

proliferation of titles.

"[Marvel]

did flood the market, but remember, this was that

period (...) where Marvel suddenly decided to put out

a whole bunch of books (...) trying to get market

share (...) lots of stuff came out in the '70s

because of this approach." (Roy Thomas, in

Cooke 2001)

DC realized what was happening, and Carmine Infantino,

DC's publisher since 1971, tried to stem the tide in 1973

by emulating Marvel and putting out a few new (Shazam,

Prez, Plop) as well as some reprint titles in order

to boost DC's output and keep from getting pushed off of

those shelves. Unfortunately, the success of both

offerings was somewhat underwhelming, and most of the

reprint titles only saw a handful of issues before being

cancelled.

|

| |

But there was a logic to the

failure of the DC reprint titles launched in 1973

- the Silver Age material they featured simply

wasn't hitting home with current readers any more

- and Infantino knew it.

"The DC books

were very sterile-looking in those

days." (Infantino & Spurlock,

2001)

However, in terms of overall sales figures,

however, DC didn't fare that badly. In 1973,

Marvel roughly sold a total of 6.5 million comic

books, with DC at 5.5 million copies. But the

comic book industry as a whole was struggling and

in a downward spiral; by 1975 Marvel lost $2 million a year (Daniels,

1991), whilst DC's business returns were in the

red for $1 million. Although doing only half as

badly as Marvel, Infantino was fired by the

Warner Brothers top brass (Howe, 2012).

|

|

Carmine

Infantino

(1925 - 2013)

|

|

| |

| Legion of Super-Heroes

was the very first of the 1973 reprint titles, launched

with a February cover date, and at least initially (for

the first two issues) supplied with new covers by Nick

Cardy. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Its main feature

- no surprise, given its title - was material

starring the Legion of Super-Heroes which had

previously been published between 1964 and 1966

in Adventure Comics (with stories from Action

Comics dating from 1957/58 added for the

final two issues). Legion of Super-Heroes

switched from monthly to bi-monthly publication

after two issues, before ceasing publication all

together after a mere four issues.

Although these were mostly newer

stories from less than ten years ago (and

therefore pretty much what Marvel was repackaging

in its superhero reprint titles), the problem was

that this 1960s material featured stories and

artwork with heroes (e.g. Matter-Eater Lad) and

villains (e.g. Computo the Conqueror) that had

more of a 1950s feel to them. That is presumably

what the majority of comic book readers in 1973

felt too, given the extraordinary short life-span

of this title.

|

|

| |

|

|

Only

the two final issues of Legion

of Super-Heroes were

packaged into DC's

SUPER-PACs of 1973 (B-4

and B-6). |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

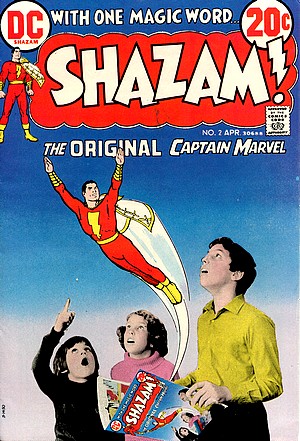

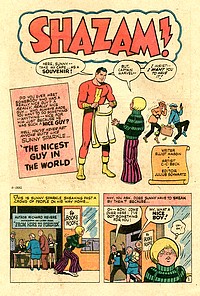

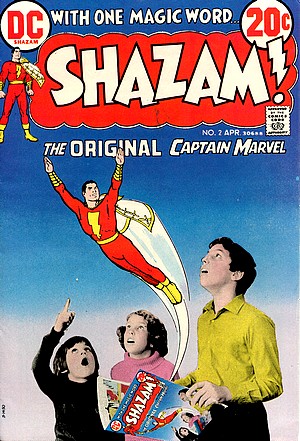

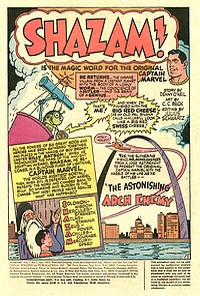

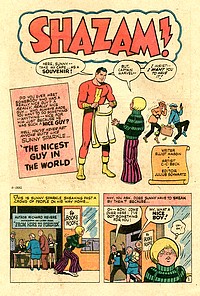

SHAZAM #2

April

1973

(monthly, with the

exception of Jan., March, July

and Nov.)

On Sale: 15 February 1973

Editor -

Julius Schwartz

Cover - C.C. Beck (pencils &

inks) & Jack Adler

(photograph & assemblage)

SHAZAM:

"The Astonishing Arch

Enemy" (10 pages)

Story - Denny O'Neil

Pencils, Inks, Lettering - C.C.

Beck

SHAZAM:

"The Nicest Guy in the

World" (7 pages)

Story - Elliot Maggin

Pencils, Inks, Lettering - C.C.

Beck

SHAZAM:

"The

Original Captain Marvel Fights

Niatpac Levram!"

(6 pages)

Story - Otto Binder

Pencils, Inks, Lettering - C.C.

Beck

(reprinted from

Captain

Marvel Adventures #139,

December 1952)

|

|

|

|

| |

| PLOT

SUMMARIES -

Mr. Mind destroys a museum to get his

glasses back from it and then plans to destroy the United

States but is stopped by Captain Marvel with the help of

the Saint Louis Arch, which he uses as a tuning fork;

Bank robbers give Sunny Sparkle their loot; Wizzo uses

magic to animate Captain Marvel's mirror image in an

attempt to become a master magician. |

| |

|

| |

| As editorial director Carmine

Infantino was gearing up DC for a slew of reprint titles

to hit the spinner racks in 1973 in order to try and push

back Marvel's numerical and therefore visual and

commercial dominance at comic book points of sale, it was

obvious that DC also needed new titles if there was to be

any chance of competing with their mighty rival. |

| |

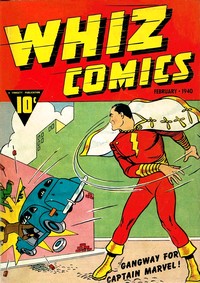

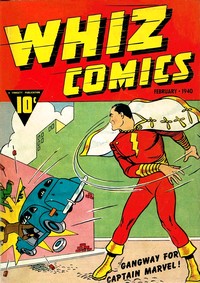

Whiz

Comics #2

(February 1940)

|

|

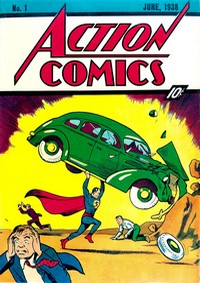

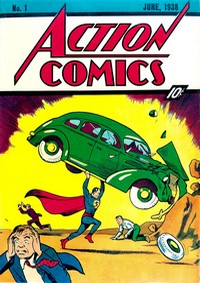

One

such title launched in early 1973 was Shazam!

- although "new" wasn't exactly

accurate in this case, as DC decided to license

the original Captain Marvel from Fawcett and

bring him back after a publication hiatus of

nearly 20 years - a move full of irony since it

had been DC who had put an end to the character's

adventures (and indeed Fawcett's entire line of

superhero comics) in the courts by 1954, claiming

- not without reason if you compared the covers

of Action Comics #1 and Whiz Comics

#2) - that Captain Marvel was ripping off

Superman. Unable to use the original title

since Marvel had gained the copyright to the name

back

in 1967, DC went with the magic word that

transforms adolescent radio

news reporter Billy Batson into the

"World's Mightiest Mortal". A

"continual drumbeat" from fans for the

character's return along with a built-in fanbase

(Sacks, 2014) seemed too good an opportunity to

be missed, and DC went all out in hyping up the

retrun of Captain Marvel in Shazam

(officially the title came with an exclamation

mark).

|

|

Action

Comics #1

(June 1938)

|

|

| |

Assigned veteran editor Julius Schwartz added another

coup to the launch by bringing on the original

artist, Charles Clarence (C.C.) Beck, giving DC’s

revival an added boost of credibility - and even more

publicity (Smith, 2010). This move also settled other

matters:

"The question we had

at the time was whether we should do what they had

before and see if it worked. They decided to go that

route, and promoted the hell out of it!"

(Elliot Maggin in Smith, 2010)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In essence, this meant an

entirely retro take on both visuals and

storylines, meaning simple and almost cartoony

artwork along with just as quirky - and often

over the top - plots. Shazam

#2 featured two original stories and one reprint,

and even though the latter was from 1952, they

were almost impossible to tell apart.

This combination spoke to

older fans (who knew the original material) and

very young readers, but held little appeal to

most regular comic book readers.

|

|

"It was an

anachronism (...) The audiences were in a process of

getting older quicker. The more successful comic

books were beginning to adapt to that, to cater to

that college-age audience and older. And I think

Captain Marvel got caught in the wrong age at the

wrong time, and it was not working for the people who

were buying comic books." (Michael Uslan in

Smith, 2010)

|

| |

| Shazam sold well

initially, but before long sales dropped precipitously

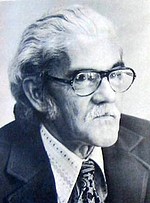

(Sacks, 2014). Matters were further complicated by C.C.

Beck's interference in the creative process, leading to

frustration amongst writers (who saw their script changed

without notice) and ultimately also with editor Julius

Schwartz. |

| |

"The

conflict between Beck and the

other creators reached a

boiling point when he refused

to draw the scripts for

[Shazam #10] (...) At Nelson

Bridwell’s suggestion, Beck

did his own story (...)

Bridwell’s [subsequent]

rewrites to the script didn’t

sit well with Beck, and he

washed his hands of the

book." (Smith,

2010)

DC had

enough, and Beck was out. As of

issue #12 (May 1974), Shazam

was reduced to a bi-monthly

publication schedule,

periodically only featured

reprints, and was finally

cancelled in May 1978 with issue

#35. During all of that time,

Beck was essentially at war with

the contemporary creators and

publishers of comic books, as can

be seen from a list of

"seven deadly sins of comics

creators" which he had

jotted down in the 1980s and were

featured in Alter Ego (Vol.

3) 36 (Hamerlinck, 2000). Beck

stipulates that comic book

artwork should be visually simple

("Billy Batson and

Captain Marvel were drawn in

cartoon-comic style because they

appeared in comic books")

|

|

C. C. Beck

(1910-1989)

|

|

|

|

| |

| Beck advocated (and quite

uncompromisingly so) that comics should stick to their

roots, and voiced a clear distaste for artists who went

beyond the conventionalities established in the 1930s and

1940s ("artists who show people bursting out of

their panels and leaping off the pages are destroying the

illusion that the reader is seeing an exciting story

unfolding itself on the printed page"). He had

a distinctly old school approach to comic books - and

unfortunately for him, that just didn't sell anymore. |

| |

| |

|

|

DC's

(initial) drive to push Shazam

any which way they could

can also be felt in their

SUPER-PACs of 1973 and

1974, where the title was

included frequently,

starting with Shazam

#1. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

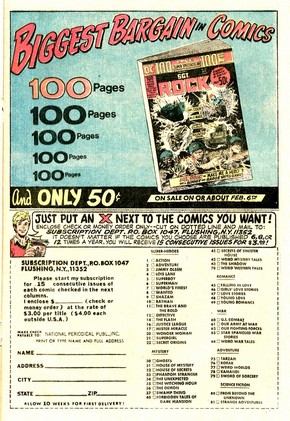

| There were many things that set

DC apart from Marvel in the early 1970s, but one very

salient aspect was DC's lack of any regular editorial

feature across its titles through which editors would

communicate with their readership (as Marvel and Stan Lee

did with their famous Bullpen Bulletins); DC's

interaction with its fans and readers was limited to the

letters pages, whilst plugs for other titles were

essentially restricted to in-house ads. If you picked up

this April 1973 B4 SuperPac, you came across the

following. |

| |

Left from Batman

#248, center & right from Legion of Super-Heroes

#3

|

| |

|

| |

| FURTHER

READING ON THE THOUGHT

BALLOON |

| |

| |

|

|

"Comic

packs" not only sold well

for more than two decades, they

also offer some interesting

insight into the comic book

industry's history from the 1960s

through to the 1990s. There's

more on their general history here. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

An overview

and analysis of all the 1973

Super Pacs is available

here. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

You can read

more about the 1973 "war of

the shelves" between Marvel

and DC here. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| |

| COOKE

Jon

B. (2001) "Son of Stan: Roy's Years

of Horror", in Comic Book Artist #13 DANIELS

Les (1991) Marvel: Five

Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics,

Harry N. Abrams

EVANIER

Mark (2004) "On

the Passing of Bob Haney", News From

Me, published online 7 December 2004

EVANIER Mark (2007)

"More on Comicpacs", News From Me,

published online 2 May 2007

FOERSTER Jonathan

(2010) "Marvel Comics' miracle

man set up business' success", Naples Daily

News, 30 May 2010

GREENFIELD

Dan (2024) "13

Reasons Batman Artist Bob Brown Deserves More

Credit", 13th Dimension,

published online 5 March 2024

HAMERLINCK

P.C. (2000) "The

Seven Deadly Sins of Comics Creators, by C.C.

Beck", Alter Ego (vol. 3) #6,

TwoMorrows Piublishing

HANDZIUK Alex

(2019) "An

Interview with Legendary Creator Denny O'Neil -

The father of Modern Day Batman", cgmagonline.com,

published online 16 March 2019

HOWE Sean

(2012) Marvel Comics - The Untold Story,

Harper Collins

INFANTINO Carmine,

with J. David Spurlock (2001) The Amazing

World of Carmine Infantino. An Autobiography,

Vanguard

KINGMAN

Jim (2011) "What Bob Brown did for

Batman", Back Issue #50, TwoMorrows

Publishing

O'NEIL

Denny, Neal Adams, Paul Levitz & Mark Evanier

(2011) "Pro2Pro: Dark Rebirth", Back

Issue #50, TwoMorrows Publishing

PEARSON

Roberta E. & William Uricchio (1991)

"Notes from the Batcave: An Interview with

Dennis O'Neil", in The Many Lives of the

Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and

His Media, Routledge

SACKS

Jason (2014) American Comic Book

Chronicles: The 1970s (1970-1979),

TwoMorrows Publishing

SHOOTER Jim (2011)

"Comic Book Distribution", jimshooter.com,

published online 15 November 2011

SMITH

Zack (2010) "An

Oral History of Captain Marvel: The Shazam Years,

pt1", newsarama.com, published

online 31 December 2010 (accessed through

Internet Archive)

WELLS

John (2012) American Comic Book Chronicles:

The 1960s (1960-1964), TwoMorrows Publishing

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

(c) 2025

The illustrations

presented here are copyright material. Their

reproduction for the review and research purposes

of this website is considered fair use as set out

by the Copyright Act of 1976, 17

U.S.C. par. 107.

uploaded to the web

17 August 2025

|

| |

|

| |

|