|

|

|

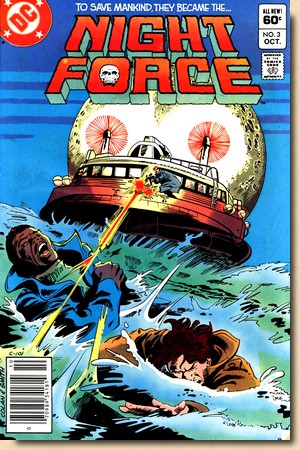

SPOTLIGHT ON SPOTLIGHT ON

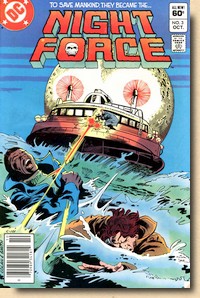

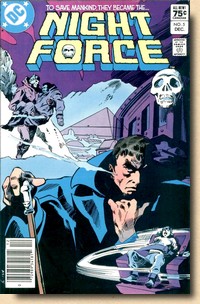

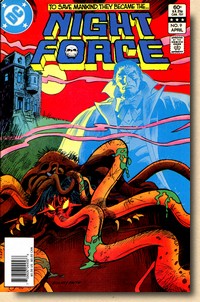

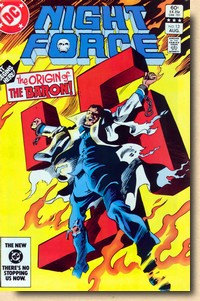

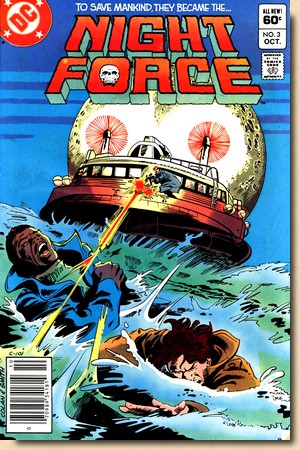

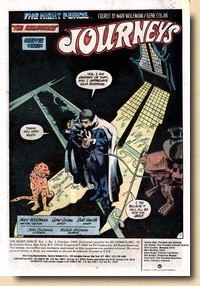

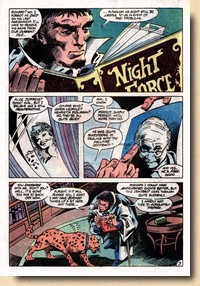

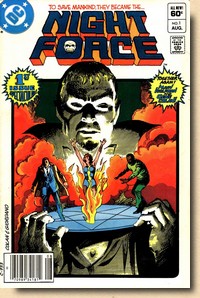

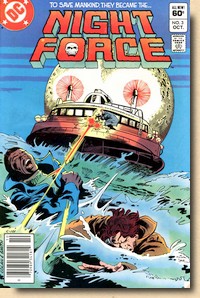

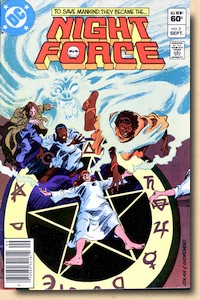

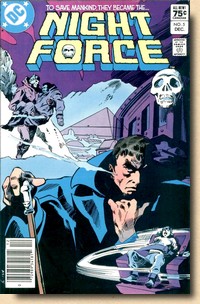

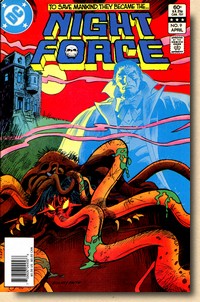

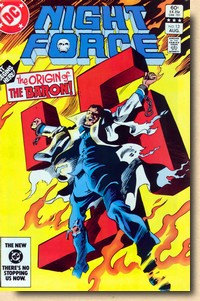

NIGHT FORCE #3

(OCTOBER 1982)

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

"The Summoning, Chapter

III: Journeys"

(23 pages)

Cover

pencils - Gene

Colan

Cover inks -

Bob

Smith

Story - Marv

Wolfman

Art - Gene Colan

Inks - Bob Smith

Colours - Michele Wolfman

Lettering -

John Costanza

Editor - Dick Giordano (Managing),

Marv Wolfman

on sale

22 June 1982

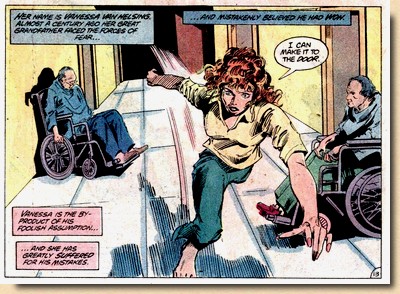

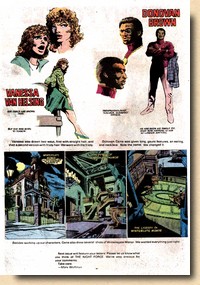

STORY OVERVIEW - When Vanessa Van

Helsing, great granddaughter of the famous

vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing, is kidnapped

by shadowy forces from behind the Iron Curtain,

Baron Winter sends Jack Gold, a down on his luck

journalist, and Donovan Caine, an African

American parapsychologist - who both seem to hate

each other at first sight - first to London and

then into the depths of Siberia to rescue her.

|

|

| |

| |

THE SUPERNATURAL

COMIC BOOK TITLE OUT OF TIME

It was late 1980, and

"Gentleman" Gene Colan was leaving Marvel for

DC, feeling miserable after a protracted struggle he had

endured with Jim Shooter since the latter had become editor-in-chief in 1978 (Irving, 2010).

At DC, he met up again with Marv Wolfman, who himself had

left Marvel (also mostly due to Shooter) a few months

prior to Colan - as had other major Marvel alumni,

including Roy Thomas. Shooter was not only tightening the

reigns at Marvel but also pushing his own perception of

what a good comic book was, and the resulting fallout was

enormous (Howe, 2012).

"I left

because I had big problems with Shooter. Lots of

people just went right over to DC (...) Marv had

already gone over, and he wanted me to come along

(...) I thought maybe I could hack it with Shooter

around, but it just went from bad to worse, so I had

to leave. Well, I went over to DC and I did Night

Force."

(Gene

Colan, in CBR Staff 2000)

DC was determined

to make the most of Colan's shadowy and moody visuals,

and immediately assigned him to Detective Comics and Batman

(where Gene Colan was formally introduced to the DC readership

on the splashpage of Batman #340, cover dated October 1981 but

on sale as of 16 June 1981).

|

| |

|

Spotlighting

the exodus of A-list creative talent from Marvel

to its ranks, DC was also eager to promote the

reunion of Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan, who of

course had been nothing short of a "dream

team" back in the 1970s on Marvel's Tomb

of Dracula.

There

was, however, a slight problem with this - to all

intents and purposes the horror genre had

withered and died away by the time Colan and

Wolfman left Marvel.

Nevertheless, Wolfman

felt confident that a supernatural-themed comic

book could still be successful, and DC gave it

all the publicity it could while also resorting

to a somewhat unusual introduction of the Night

Force - as

a 16 page preview in New

Teen Titans #21 (a title with which Wolfman was

enjoying a highly successful run at the time,

thus giving the project an extra boost).

|

|

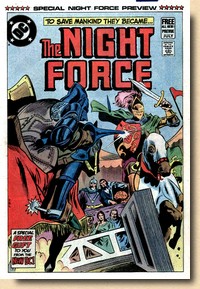

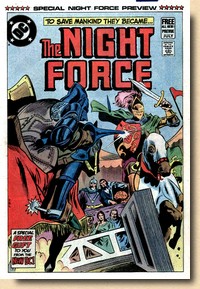

Preview in New

Teen Titans #21 (July 1982)

|

|

| |

|

Ultimately, DC blew its trumpet

on Night Force in a way which was highly

reminiscent of the Marvel hyperbole of the 1970s. |

| |

|

|

It wouldn't

be the only thing that would remind those in the

know of Marvel when Night Force #1 went

on sale May 20th 1982, cover dated for August

1982. As a matter of fact, Marv Wolfman himself

brought up more parallel lines in a

first-issue-editorial.

After an overview of the

history of horror comics, Wolfman

dedicated no less than three entire

paragraphs to highlighting the

(undisputed) merits of Tomb of

Dracula before pointing out that

"not

only did Gene [Colan] and I come to

DC, but so did Dracula's virtually

full-time letterer, John Costanza

(...) Also, Dracula's colorist,

Michele Wolfman (yes, my wife!) has

returned to the dye-pot to add the

proper mood we seek."

Although Wolfman emphasized repeatedly

that "Night Force is something

different in comics", readers

could probably be forgiven for thus

expecting this

creative

team to somehow continue the legacy of Tomb

of Dracula

(Francoeur,

2013). The fact that

one of the main

characters introduced in this first issue

was Vanessa Van Helsing, great

granddaughter of Abraham Van Helsing

(which made her a sister of Rachel Van

Helsing from Tomb of Dracula)

didn't disperse any such expectations

either.

|

|

|

All in

all, it looked a lot like "flipping the

bat" (forgive the pun) to Jim Shooter at

Marvel - as indeed a lot of fans were quite

expecting to see, given that the discontent and

even hurt felt by Wolfman and Colan was no

secret.

|

|

| |

But the fact of the matter was

that Wolfman meant what he said - Night Force

was to be a totally different type of mystery

plus horror plus supernatural title.

"Suffice it

to say that THE NIGHT FORCE is something new,

something very different, something risky,

and something we are all very proud of. Will

we succeed? I don't know. Horror comics are

on the outs today, yet we feel this is more

than a horror comic. We have adventure,

thrills, and more importantly, stories about

people." (Wolfman, 1982)

|

|

|

|

| |

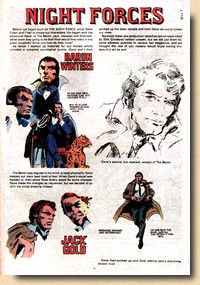

| At the centre of the Night Force

was Baron Winters, a mysterious

sorcerer who lives in eerie Wintersgate Manor, located in

the Georgetown area of Washington DC. The building functions

as a gateway portal to different locations and time

periods, enabling the Baron to move to any other location

and/or time era - with the exception of actually just

stepping out onto the lawn around Wintersgate Manor in

the here and now, where he was somehow restricted to

dwelling inside the manor's walls. |

| |

| |

REVIEW & ANALYSIS

|

| |

| Night Force #3 starts out in Washington DC,

from where the mysterious Baron Winter sends a journalist

who has fallen on hard times (Jack Gold) and an African

American parapsychologist (Donovan Caine) to London, from

where their assignment - to find and free kidnapped

Vanessa Van Helsing, great granddaughter of the famous

vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing - takes them

behind the Iron Curtain to Siberia. Obviously

still an early issue in the series, Night Force

#3 highlights both the strengths and weaknesses of the

underlying concept in an almost exemplary way. Everything

seems to be "as well as": the plot moves fast

but feels strangely disoriented, the characterization of

Gold and Caine and their clear disliking of each other

goes from interesting to tedious rather quickly, and the

mystery behind both the Baron and Vanessa Van Helsing is

both intriguing and lifeless at the same time.

In spite of the creative talent

involved and Wolfman's enthusiasm, Night Force didn't

work as intended. There are some die-hard fans who will

disagree, but the ultimate proof of the pudding for comic

books is early cancellation, and in the case of Night

Force this came after 14 issues - even though Marv

Wolfman saw the reason for this in a substantially wrong

perception of the sales figures.

|

| |

"DC wanted to

have Night Force be one of the first

direct-sales books, where I believed it

should be newsstand only. I felt the comic

shops appealed primarily to the superhero

fans while Night Force would appeal more to

the casual mainstream reader, who might not

have bought comics otherwise. We got the

comic-book shops' sales early and it was

cancelled based on those, but when the

newsstand sales finally dribbled in we

actually sold pretty well." (Marv

Wolfman, in Kingman 2008)

So did DC let the axe come

down somewhat prematurely? The real question is:

was DC looking to put out a series that wouldn't

sell too well but be critically hailed as a

groundbreaking milestone of innovation in comic

books? And if so, would they be happy to put the

"masters of the macabre", just recently

lured away from rival Marvel, to work on such a

title? It is hard to see any of that holding much

appeal for DC, who clearly wanted Wolfman and

Colan to come up with a series that would be as

successful as the one they had put out for Marvel

with Tomb of Dracula.

But that

wasn't going to happen. The high tide of the

horror genre in comic books had come and, most

importantly and unfortunately for Night Force,

gone. The decision makers at DC had probably

hoped for some sort of revival, but a series that

had a number of problems almost built into its

DNA was not going to trigger that - something

that Marv Wolfman himself was very much aware of

and frank about.

|

|

| |

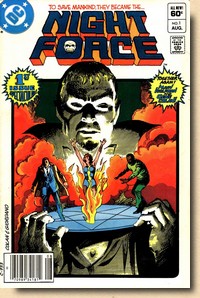

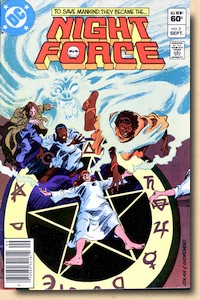

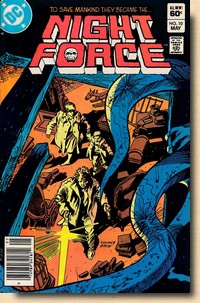

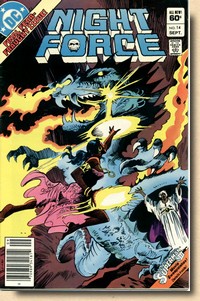

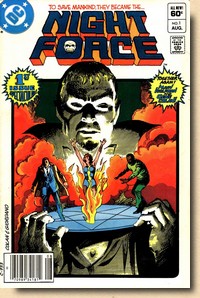

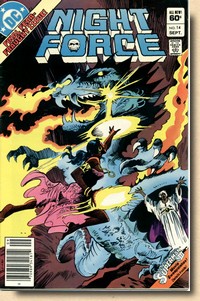

Night

Force (vol 1) #1

(July 1982)

|

|

One central problem that plagued

the series from its outset was the lack

of a stable and regular cast of characters

- even though the revolving door concept as

explained by Wolfman made sense and sounded

perfectly good and interesting.

"There are

regular characters, but then again, there

aren't. You see, the Baron will call together

his Night Force as he needs them. Someone may

be called in for one storyline but they might

not be needed for the next."

(Wolfman, 1982)

Unfortunately, it didn't

work the way it was intended to, which was

primarily due to the fact that the pivotal

persona - Baron Winters - was often so vague and

even elusive that he ultimately provided a very

weak link to the various other characters and

storylines.

"Baron

Winters is obsessed with the balance of good

and evil. He doesn’t really care which

side comes out victorious in individual

battles, as it doesn’t matter, as long

as things are balanced." (Marv

Wolfman, in Salvatore 2018)

"I was

planning to do some kind of origin [of Baron

Winters] at some point but I always felt that

you'd never know if anything Winters said was

true or not." (Marv Wolfman, in

Kingman 2008)

|

|

| |

| This reason for his ambiguity, however, was never

explicitly revealed nor explained at the time of the

original Night Force run, and what started out

as an initially intriguing plot device soon turned into a

somewhat annoying suspicion that all those dangling

questions would most likely never be answered. Asked years later in an interview if

Wolfman was planning on revealing the reason for Winters'

inability to actually leave Wintersgate Manor, his answer

still kept the question marks floating.

"I had my reasons;

they were part of the bible I wrote. But no, I

won’t share them until I’m given the

opportunity to do another series, if that ever

happens." (Marv Wolfman, in NN 2008)

Wolfman did actually get the

opportunity, in 2012, when DC once again brought back

Night Force (after a previous - and failed - revival

in 1996/97). However, he once more chose to keep the key

to that mystery to himself.

The same lack of definition also

extended to the characters making up the Night Force team

of the first story.

|

| |

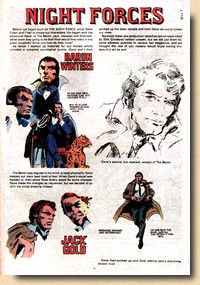

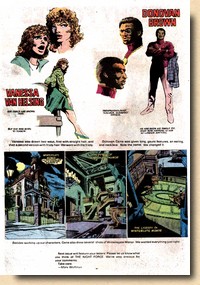

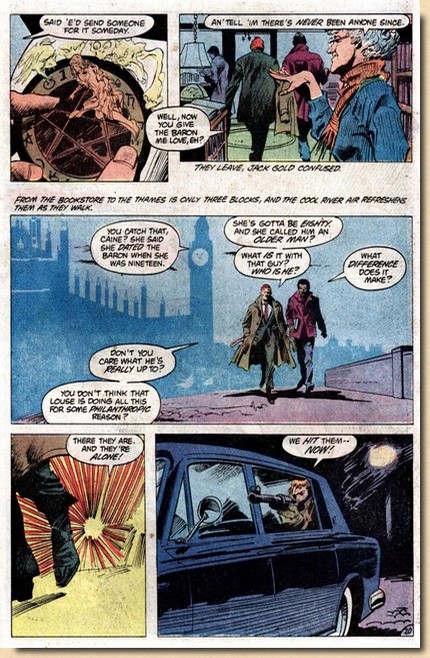

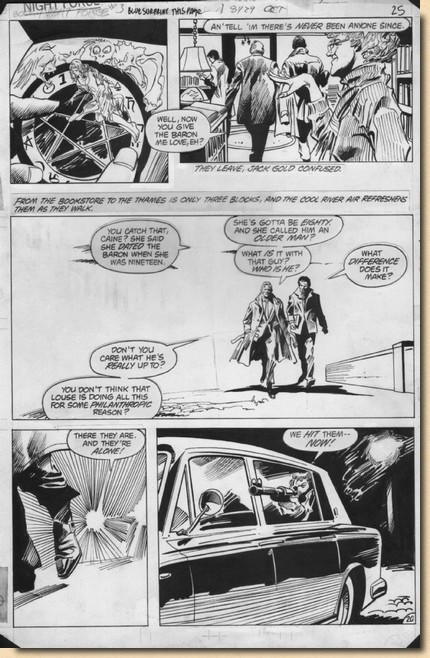

Page

24, Night Force #3

|

|

This was a shame and also

not really understandable, since a double

page feature at the end of Night

Force #3 spelled out and illustrated

the enormous amount of preparation and

design studies by Wolfman and Colan that

had gone into the creation of characters

and the setting of the title. But somehow, most of

those intricate and deep conceptual ideas

simply did not translate into

characterization or a plot that pulled

readers in. Night Force #3 is a

good example; the initial pages are

intriguing and create an interest in the

story to unfold, but once the actual

events get into gear and the characters

start to move on within the storyline, it

all begins to feel strangely detached.

Given the creative

team involved, it seems safe to assume

that a fairly large number of readers

really wanted to like this comic book,

but for some reason it just wasn't easy

to do so, and the lack of a central cast

of interesting and engaging characters

certainly didn't help.

|

|

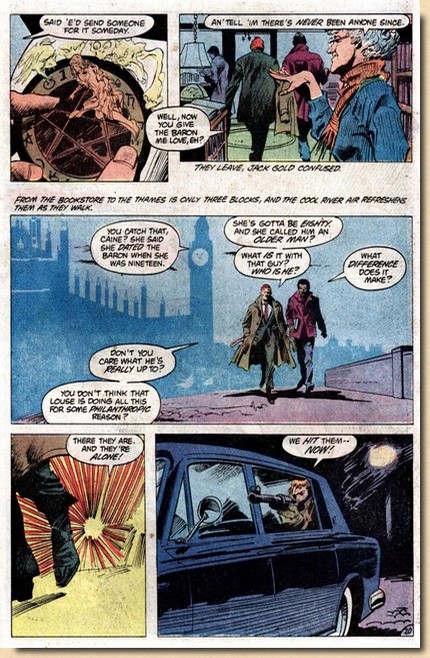

Page

25, Night Force #3

|

|

|

| |

| Wolfman was acutely aware of the

problem, and brought it up in the letters column of Night

Force #2 when he was telling readers (again) about

the potential tripwires the title faced [bold highlight

added for this write-up]. |

| |

|

|

"Our

second strike against us (as the experts

tell us) is our lack of

a regular cast. They

say readers want characters to be in

every issue. They want their heroes clear

cut. Well, THE NIGHT FORCE has neither

(...) That might prove to be a problem,

but we think it's one of our greatest

strengths (...) Our heroes are not always

heroes in the strictest sense of the

word, therefore two more strikes against

us (or so the experts say)."

(Marv Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #2) |

|

|

| |

| Experts aren't always right, but

on this occasion, and unlike what Wolfman was

suggesting/hoping, they may have not been entirely off

the mark. |

| |

| Another problem was an extremely extended

first story arc. Including the preview in New

Teen Titans #21, it took eight and a half issues to tell,

which even by today's standards (where writers plan their

stories in five or six issue segments in order to fit the

trade paperback format) is a highly strung out storyline.

But in 1982, an introductory storyline spread out over 9

months of real time was, quite simply, way out there. |

| |

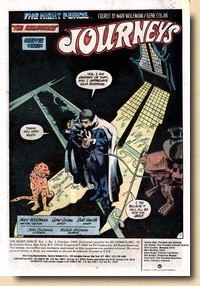

Splashpage,

Night Force #3

|

|

The problem with this

approach was that it required readers to

really be (and remain) invested in the

characters and the tale that Wolfman and

Colan were presenting to them. If they

weren’t drawn in after the first few

issues, they would drop off, most likely

never to return. At

the same time, such a long initial story

arc meant that if Night Force #3

was the first issue of the series you

picked up, you might have a problem

getting into things as there was no real

recap of previous events worth

mentioning.

Given the type of

plot Wolfman was weaving (one that was

aimed at a more mature readership), this

was actually understandable, but the

extended length of the initial arc

amplified the risk of not enabling new

readers to come on board late and still

understand what was going on. It also

meant that new readers couldn't be banked

on to make up for those who had left

after a few issues.

|

|

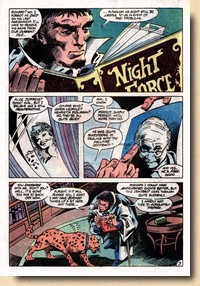

Page

3, Night Force #3

|

|

|

| |

| Marv Wolfman highlighted the

problems associated with this concept mself in the

letters column of Night Force #2 [again, bold

highlights added for this write-up]. |

| |

|

|

"Our

stories are multi-part

stories. They require

you to be with us every issue.

And since we're not recapping everything

on page two (as most comics do) we're

not making it easy for new readers

(although we believe new readers can pick

up the storyline at any rate)."

(Marv Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #2) |

|

|

| |

Of course Wolfman had good creative reasons for such

an approach.

"In most comics

change comes slowly if at all. Not so here. One of

the reasons is the approach we're taking. Each story,

as we stated, takes several issues. They will

progress like a novel; characters will change during

the course of the storyline (...) This is radically

different from the way comics are usually handled,

and this is the one thing we're proudest of in our

new creation." (Marv Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #2)

|

| |

| Unfortunately for Wolfman and DC,

it was another innovative gamble that simply didn't pay

off. |

| |

Another problem was rooted in the fact that

Tomb of Dracula

cast too long a shadow over the series.

It must have been clear to everyone right from the

beginning that a horror/supernatural title by Marv

Wolfman and Gene Colan would instantly and continuously

be compared to Tomb of Dracula. There was no way

of ignoring this, and it would always be something of a

tightrope walk (not the least since DC's public relations

people were clearly pushing the

"Wolfman-Colan-Horror" clout).

"I was looking for

another book to do and felt I’d like to create

my own horror title and push the boundaries a bit

more than I had with Tomb of Dracula. I really wanted

to try something different (...) The idea was to

write for the older audience, with darker and more

realistic stories than had been done at that

point." (Marv Wolfman, in Kingman 2008)

The catch 22 here was, of course,

that the more Tomb of Dracula got mentioned, the

more difficult it became to avoid having everybody

compare the two titles.

|

| |

|

|

"Permit

me to discuss (...) at some length Marvel's

The Tomb of Dracula

(...) Modestly, Dracula consistently

garnered rave reviews (...) and has since

been often hailed as a

comics classic. I say

modestly because I wrote

The Tomb of Dracula for

the majority of its run (...) but even

that was rivaled and beaten by artist Gene

Colan who drew the comic from its very

first issue until its last,

nine years later (...) Dracula was not

cancelled until after I left Marvel and

others tried to discover just what it was

we did to make succeed what was

ostensibly only a vampire comic."

(Marv Wolfman, Night

Forces, Night Force #1) |

|

|

| |

| Wolfman was right about

everything he stated there (except that Tomb of

Dracula was actually cancelled while he was indeed

still at Marvel, providing what was most likely the

ultimate fallout with editor in chief Jim Shooter and the

straw that broke the camel's back, leading to his

departure for DC), yet clearly misjudged the effect of

these repeat references to TOD (including the previously

quoted reference to its original creative team all being

reunited for Night Force). Hints were seen and

taken and false expectations raised as a consequence,

even if none of it was ever intended that way. |

| |

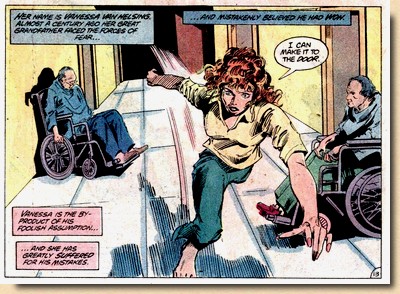

| But the single biggest mistake in

this context must be Wolfman's decision to introduce a

character named Vanessa Van Helsing. |

| |

Night

Force (vol 1) #1 (July 1982)

Page 13, introduction of Vanessa Van Helsing's

name

|

|

Seen as "a nod to their

previous Tomb of Dracula work" (Dallas,

2013), having a persona who was the sister of one

of the main characters of Tomb of Dracula

(Rachel Van Helsing) almost invalidated any claim

that this was not, in no shape or form, intended

to be a continuation. At the least, there was now

a link. Wolfman himself

encouraged such a view. Right off the bat (again,

pardon the pun), in Night Force #1, he

introduces Vanessa as a patient at a mental

institution in Georgetown.

A few pages later, it is

not only revealed that her full name is Vanessa

Van Helsing, but this is combined, in the very

same panel, with Wolfman's exposition that "almost

a century ago her great grandfather faced the

forces of fear... and mistakenly believed he had

won."

Anybody who had read the

final issue of Tomb of Dracula could be

forgiven for thinking that this was as direct a

reference to the very last panel of that comic

book that you could possibly get.

|

|

| |

| Things got even more complicated (some might say

convoluted) when Night Force #13 revealed that

the Baron was Vanessa's father. The statement as such is

made in a context which makes readers assume it's another

one of those occasion where the Baron is strategically

not telling the truth in order to confuse people, but at

least for a moment Wolfman throws out the thought to

readers that Baron Winters could be - Abraham Van

Helsing's grandson. An impossibility in the context of

Bram Stoker's novel, this again leaves only Marvel's Tomb

of Dracula (where, of course, Abraham Van Helsing

does indeed have a great granddaughter) as reference

point. The crux of all of this was

that Night Force had indeed nothing to do with Tomb

of Dracula, so any such expectations would lead to

disappointment. But then the shadow of the tales of the

vampire count loomed big and long over Gene Colan too,

who couldn't quite detach himself from his previous work

on Tomb of Dracula either.

|

| |

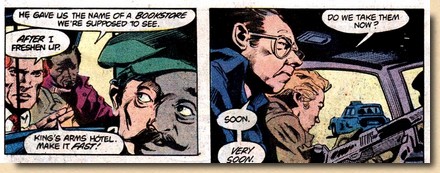

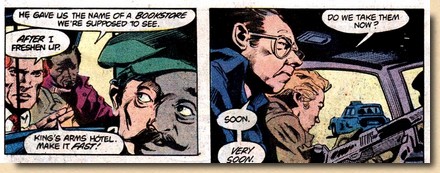

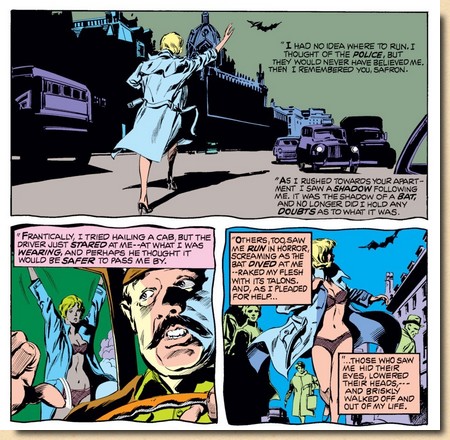

The final panel of page

18 (above) and the first two panels of page 19

(below) from Night Force #3 show Jack Gold and

Donovan Caine arriving in London and hailing a

cab.

A comparison

with the first two panels of page 11 from Tomb

of Dracula #24 (right) reveals some striking

resemblances.

|

|

|

|

| |

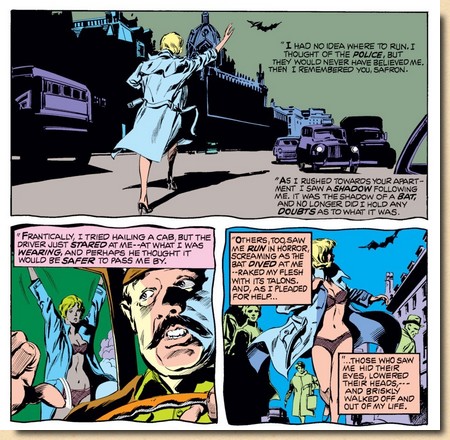

Gene Colan's artwork was of the usual high quality,

but in comparison to Tomb of Dracula, the

"DC house rules" were quite evident and

prevented the finished product from having the famous

somber and shadowy feel which had made Marvel's title so

effective and loved by fans.

"DC

was a tough outfit. They wanted an in-house look for

all of the artwork, and they wanted the artists to

draw somewhat the same." (Irving, 2010)

As

a result, DC's "clean" final artwork style

stifled Colan's complex pencils much more than any inker

at Marvel ever had.

"My

style just doesn't lend itself well to inking. I

always had a lot of in-between shading that the inker

didn't know how to interpret or just didn't want to

bother. It was very time consuming. I've seen it

described as cinematic, which is a description I

really like because I do try to make it look like a

movie." (Gene Colan, in CBR Staff 2000)

|

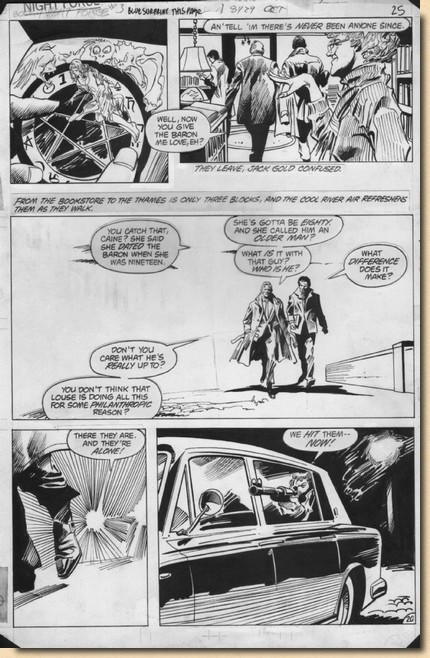

| |

Original

artwork by Gene Colan for page 20 of Night Force

#3 (scanned from the original), and as it

appeared in print;

Note that the pasted word balloon of the first

panel had come loose and was subsequently lost

over time

|

|

| |

| |

FADING INTO THE NIGHT

|

| |

| Night Force was launched with great hopes in

early 1982, but ended in all-around disappointment by

mid-1983. The only solace for all the creative talent

involved was that it hardly came as much of a surprise. As Marv Wolfman had pointed out so

often and repeatedly, Night Force was different.

The dissimilarity to most other comic book titles

included how openly its author used editorial space to

convey the struggles and problems he assumed Night

Force may well face.

|

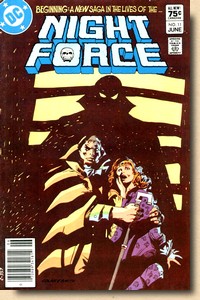

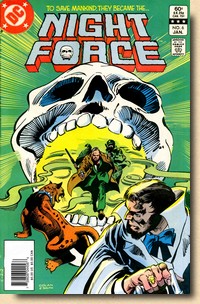

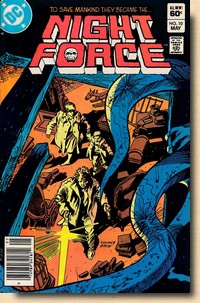

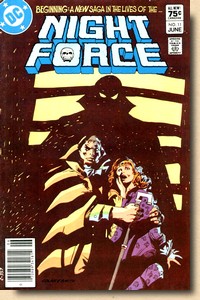

Night

Force #1

(July 1982)

Night

Force #3

(October 1982)

|

|

"In a

market that seems not only to want

super-heroes, but seemingly wants only

super-heroes, a

mystery/supernatural/horror comic

such as THE NIGHT FORCE is obviously

a risky gamble." (Marv

Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #2)

This even went as

far as appealing to readers to really

throw in their weight in order to support

the title.

"Whether

we survive the economic crunch and

the current glut of competing comics

or not we know we'll have tried our

hardest to provide something good,

something new, and something we

obviously care about a lot. But we

need you if we are to survive. You

see, THE NIGHT FORCE has so much

going against it that we can only

hope you people will like us, follow

us, and tell your friends about

it." (Marv Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #2)

Of course Stan Lee

had done pretty much the same thing for

the past two decades, but his appeals

always sounded slick and positive (of

course you would want to share the good

news with your friends). But Marv Wolfman

was far too level-headed to resort to any

such hyperbole. However, his no-frills

approach with readers came with the

downside that his statements and messages

could (and indeed did), at times, take on

a rather sombre or even downright

negative tone.

"That's

a lot of problems, so why did DC go

out on the proverbial line and

publish such a risky comic? Why turn

out a non-super-hero comic? Why

simply not follow the lead instead of

creating a new approach? Why? Because

we think THE NIGHT FORCE is a good

comic. It's that simple. We think

comic book readers will buy something

that is good even if our protagonists

don't wear capes. We think solid

story-telling, dynamic artwork, and

the best product we can turn out will

sell. At least we hope so."

(Marv Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #2)

|

|

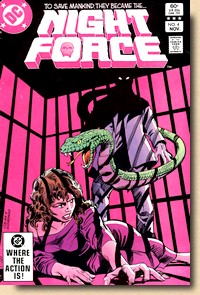

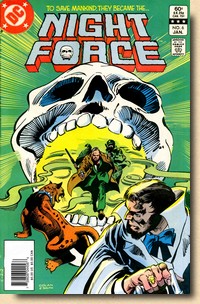

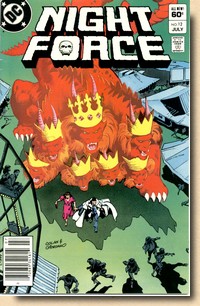

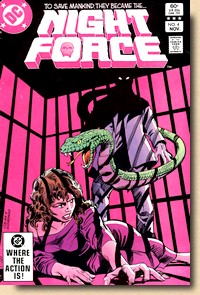

Night

Force #2

(September 1982)

Night

Force #4

(November 1982)

|

|

|

| |

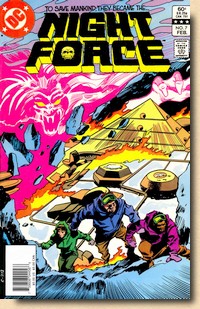

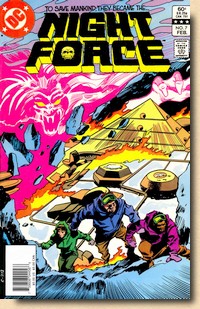

Night Force #5

(December 1982)

|

|

Night Force #6

(January 1983)

|

|

Night Force #7

(February 1983)

|

|

Night Force #8

(March 1983)

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

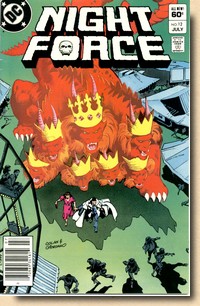

Night

Force #9

(April 1983)

|

|

But regardless of content

quality, the sales figures of Night

Force did not match the hopes of

Wolfman and the expectations of DC. After

seven issues, the length of storylines

was changed to more conventional formats.

"Our

first storyline is over and our

second begins. After this 2½-parter,

which ends in issue #10, we'll

continue doing several shorter yarns

- one and two parters at most -

before plunging ahead with another

multi-parter. Why? Well, despite the

incredible mail reaction to THE NIGHT

FORCE, sales are a bit sluggish, and

we think several smaller stories will

help allow new readers to see THE

NIGHT FORCE in action before making

the demands of another six to eight

part novel." (Marv Wolfman,

letters

column, Night Force #8)

Clearly the

extended initial storyline had cost Night

Force quite a few potential and

actual readers, and now Wolfman and DC

could only hope that the damage could be

contained.

|

|

Night

Force #10

(May 1983)

|

|

|

| |

But sales continued to indicate that the risks

Wolfman had taken (and pointed out repeatedly in issues

#1 and #2) had now truly come to not just haunt, but in

effect sink the Night Force.

"With our next issue,

which concludes the current storyline, THE NIGHT

FORCE comes to a sad ending. We just couldn't bring

together enough readers to keep NF going." (Marv

Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #13)

Wolfman was at least able to

sweeten the bitter news a bit by pointing out that

"NIGHT FORCE isn't

dead... starting next year we will be releasing THE

NIGHT FORCE as a four-part mini-series, one each

year." (Marv Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #13)

That mini-series would, however,

never see the light of day, and so Night Force

#14 (September 1983) truly ushered in the end.

"This is it, the

final issue of NIGHT FORCE. We leave this title with

great regret and sorrow (...) There may be other news

concerning THE NIGHT FORCE coming from DC within the

next months, so please keep alert. If things pan out,

the best is yet to come." (Marv Wolfman, letters

column, Night Force #13)

|

| |

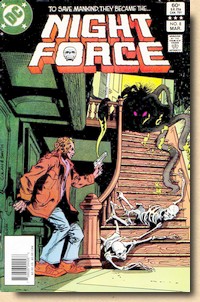

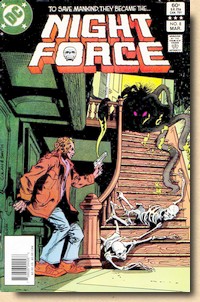

Night Force #11

(June 1983)

|

|

Night Force #12

(July 1983)

|

|

Night Force #13

(August1983)

|

|

Night Force #14

(September 1983)

|

|

|

|

| |

| In the end, however, nothing

panned out, and Wolfman was left feeling very

disappointed by the cancellation of Night Force

for years - not the least because two attempts at giving Night

Force a fresh start, in 1996 and 2012, fared even

worse than the 1982/83 run. |

| |

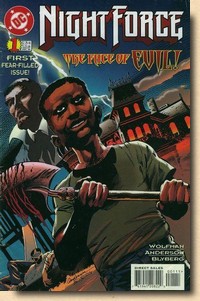

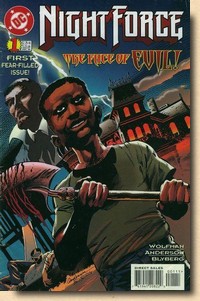

Night

Force (vol 2) #1

(December 1996)

|

|

The failure of the 1996

and 2012 runs would also seem to indicate

that it wasn't just a question of the

concept having potentially been ahead of

its time back in 1982. Wolfman himself

repeatedly stressed the fact that

"it’s

one of the most adult and complex

ideas I’d come up with and

I’ve enjoyed being the one

writer who has guided its

development. (...) If there was any

one project I’ve been most

protective of it’s probably

Night Force." (Marv

Wolfman, in West 2017)

Complexity itself

doesn't, however, automatically explain

the failure of Night Force

(since it certainly was an important

element in the success of Tomb of

Dracula). The letters pages (which

Wolfman insisted on calling letters

columns) were always full of (often

even unconditional) praise, but then that

would almost make it seem as though the

vast majority of individuals who didn't

like Night Force stopped buying

the title long before they could even be

bothered to write in about their

misgivings.

|

|

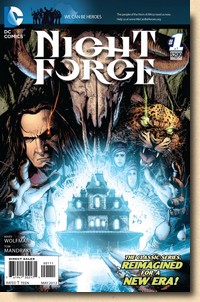

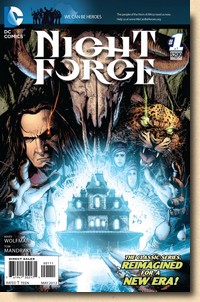

Night

Force (vol 3) #1

(March 2012)

|

|

|

| |

| Ultimately, the creative team of Tomb

of Dracula, all re-assembled for Night Force,

found that the times had changed, and they simply

couldn't repeat the magic they had previously produced. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY

BARK Jasper

(2018) "Injured Eyeballs: What the Fuck

was Night Force?",

This is Horror, published online 27 June 2018

CBR Staff

(2000) "Gene Colan Interview", CBR, published

online 6 August 2000

DALLAS

Keith (2013) American Comic Book Chronicles,

The 1980's (1980-1989), TwoMorrows Publishing

FRANCOEUR

Justin (2013) "Review of Night Force v1 ongoing series

(1982)", DC in the 80s,

published online August 2013

HOWE

Sean (2012) Marvel Comics: The Untold Story,

Harper Collins

IRVING

Christopher (2010) "Gene Colan: On Vampires, Shadows, and the

Industry", www.nycgraphicnovelists.com

KINGMAN Jim

(2008) "Forces of the Night, what Horrors they

faced: Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan's Night Force",

in Back Issue! #27 (April 2008)

NN (2008)

"Marv Wolfman Interview", Comic Book Revolution,

published online 18 December

2008

SALVATORE Brian

(2018) "Exclusive Preview + Interview: Marv

Wolfman on Bringing Night Force to “Raven: Daughter

of Darkness” #7",

Multiversity Comics, published online 20 August

2018

WEST John

(2017) "An Interview with Marv Wolfman", Comic Book Corps,

published online 26 June 2017

WOLFMAN

Marv (1982) "Night Forces", in Night Force

#1

|

| |

| |

|

| |

The illustrations

presented here are copyright material. Their

reproduction for the review and research

purposes of this website is considered fair

use as set out by the Copyright Act of 1976,

17 U.S.C. par. 107.

(c) 2022

page uploaded to the

web 21 August 2022

minor additions 12 October 2022

|

|

| |