|

|

|

THOR,

THE ETERNALS & CAPTAIN

AMERICA

BACK

TO BACK IN A

OCTOBER

1976 MARVEL MULTI-MAGS

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS |

|

Even in the early

1960s, the comic book industry

realized that in spite of the

hugely successful comeback of the

superhero genre (which had been

clinically dead for most of the

1950s) and the subsequent streak

of new creativity and enthusiasm

it generated, its traditional

sales points were fading away.

Small stores that had carried

comic books were pushed out of

business by larger stores and

supermarkets, and newsagents

started to view the low

cover prices and therefore tiny

profit margins comics had to

offer as a

nuisance. Many ideas on how

to turn these developments around

were put forward by different

publishers, but the most

successful concepts strived to

open up new sales opportunities

and markets and thus tap into a

new customer base.

|

|

|

|

| |

| One place

these potential buyers could be found was the growing

number of supermarkets and chain stores. But in order to

be able to sell comic books at supermarkets, the product

would have to be adjusted. |

| |

|

Handling

individual issues clearly was no option for these

outlets, but by looking at their logistics and

display characteristics, DC Comics (who came up

with the Comicpac concept in 1961) found

that the answer to breaking into this promising

new market was to simply package several comic

books together in a transparent plastic bag. This

resulted in a higher price per unit on sale,

which made the whole business of stocking them

much more worthwhile for the seller. The simple

packaging was also rather nifty because it

clearly showed the items were new and untouched,

while at the same time blending in with most

other goods sold at supermarkets which were also

conveniently packaged. |

|

|

|

| |

| Outlets were even supplied with

dedicated Comicpac racks, which enhanced the

product appeal even more since the bags containing the

comic books could be displayed

on rack hooks in an orderly and neat fashion. |

| |

|

|

DC's

"comicpacks" were a success -

so much so that other publishers quickly

started to copy it. Marvel produced a

series of Marvel Multi-Mags in

1968/69 but then seems to have dropped

the idea again.

However,

by the mid-1970s, the House of

Ideas had once again fully embraced the

marketing concept of selling multiple

comic books packaged in a sealed plastic

bag to a customer base which comic books

could hardly reach otherwise: people

shopping at supermarkets and large

grocery stores.

It didn't really

matter therefore that buying these three

comic books in a comicpack for say 89¢

(rather than from a newsagent for 90¢ in that case) clearly presented no

real bargain - it was the opportunity and

convenience to pick up a few comics at

the same time parents and adults did

their general shopping. Neatly packaged,

it almost became an entirely different

class of commodity.

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| The MARVEL MULTI-MAGS we are

looking at here features Thor #252, Eternals

#4, and Captain America #202, all from the

October 1976 cover date run. This meant that they were

actually on sale at newsagents in July 1976, although

there could be quite a delay in terms of actual

availability of MARVEL MULTI-MAGS

at some sales points, resulting in Multi-Mags on display

that contained "semi-recent books (typically

about nine months old)" (Brevoort, 2007).

Considering the packaging and distribution process, this

doesn't really seem too surprising.

This specific three-pack is

somewhat special in that it belongs to a small number of

late 1976 and early 1977 MARVEL MULTI-MAGS that came with a

yellow and green on white (3 comics for 89¢)

label, which display the anomaly

of not having a seal-line below the label. Heat

sealing the bag at this point served two purposes.

Firstly, it provided a somewhat strengthened label (which

of course also doubled as a hanger for most displays), but secondly - and just as importantly

- it also provided a tighter fit for the comic books, by

restricting their vertical movement inside the bag.

The lack of the sealing line below

the label is in fact a major defect with regard to how

well the packaging protects its contents, since the comic

books inside a MULTI-MAGS polybag of this type are not restricted

from moving about into the label part of the sealed bag -

quite unlike those packaged inside a "regular" MULTI-MAGS polybag (i.e. with a sealed off label).

In some cases - as the example here shows - this

protective partition was achieved (to a degree) by the

use of staples.

|

| |

|

| |

| These could

have been applied by resellers upon delivery (or even

years later by third parties); it is doubtful that this

took place at the original packaging facility. |

| |

| In any case, the staples did what they were intended

to do and prevented any excessive physical damage to the

three comic books inside the polybag - especially

noticeable when compared

to issues that were allowed to "move

freely" in MULTI-MAGS polybags affected by this lack

of a sealing line below the label.

No titles had permanent slots in

the MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS, but the

three titles packaged into this example could be found to

make reliably regular (Thor) or frequent (Eternals,

Captain America) appearances. But even with

these fairly regular titles (other examples were Hulk,

Avengers and Amazing Spider-Man) there

was never any guarantee of an uninterrupted flow of

consecutive issues - and therefore a distinct possibility

of missing out on a part of the storyline. On top of

this, the continuity of the Marvel Universe of the 1970s

was such that plots and storylines usually evolved over

more than one issue.

This

didn't exactly make the MULTI-MAGS

an ideal way of getting your Marvel comic book fix. However, one needs to bear in mind that

this was a common fate of the average comic book reader

in the 1970s Bronze Age, whether his or her comic books

came packaged in a plastic bag or as single issues from a

display or spinner rack. Back in those days, an

uninterrupted supply of specific titles was, quite

simply, not guaranteed. Not worrying too much about

possible gaps in storylines thus became something of a

routine - besides, you would usually get a recap of

"what happened so far" on the first page.

So all in

all it simply was a part of being a comic book fan in the

1970s - as were the monthly Bullpen Bulletins (which were

the responsibility of the editor-in-chief) and the

in-house advertising (often with mouth watering cover

reproductions).

|

| |

|

|

|

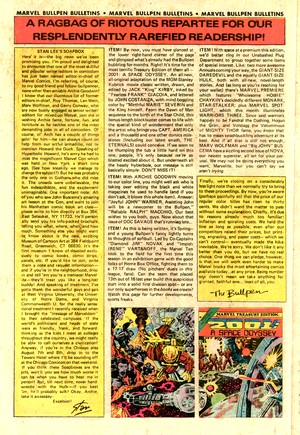

In October 1976, the

Bullpen Bulletin was still on its way

through the alphabet as far as its title

was concerned, arriving at the letter R -

which resulted in the typically

alliterative and somewhat nonsensical

title "A Ragbag of Riotious

Repartee for Our Resplendently Rarified

Readership!". The big news - and

the headline item of Stan Lee's Soapbox

column - was the promotion of Archie

Goodwin to Editor-in-Chief.

Lee also mentioned

the "illustrious list of former

editors-in-chief, Roy Thomas, Len Wein,

Marv Wolfman, and Gerry Conway" but

diligently avoided pointing out that this

position had quickly become a revolving

door affair, with those four gents

successively at the helm between 1972 and

1976 (and Conway only lasting six weeks),

and all of them stepping down to be able

to spend more time writing.

|

|

|

Also not

mentioned by Stan Lee on this occasion was the

fact that Archie Goodwin only agreed to fill the

position on the assumption that it would be

temporary, until a permanent replacement could be

found; ultimately Goodwin would resign at the end

of 1977 (Howe, 2012).

|

|

| |

| As for the actual Bullpen Bulletins' various ITEM!

bullet points, they were - as usual - mostly concerned

with new and changing assignments of various writers and

artists, as well as Marvel's ever expanding line of

titles - in this case the major push was given to the

Super Treasury Edition of Kirby's 2001: A Space

Odyssey, an adaptation of the movie. It would be

followed in December 1976 by an ongoing series of the

same title which, however, would find few favours with

readers and be cancelled after a mere ten issues. The final item of news was both bad

and not really news at all - Marvel's need (for reasons

explained in this Bullpen Bulletin in a separate box) to

raise the cover price for their regular comics from 25¢

to 30¢. Following a few tests in select markets to gauge

buyer reactions to the 5¢ hike, the higher price was

introduced as of September 1976 (cover date), i.e. the

previous month. The price for a MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS rose accordingly, to 89¢ for three

comics instead of the previous 74¢.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

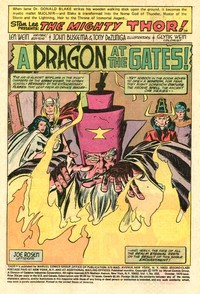

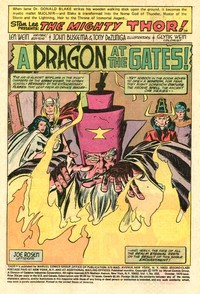

THOR

#252

October 1976

(monthly)

On Sale:

13 July 1976

Editor

- Len Wein

Cover - Jack Kirby (pencils) & John

Verpoorten (inks)

"A Dragon at the

Gates!"

(11 pages)

Story - Len

Wein

Pencils - John Buscema

Inks - Tony DeZuniga

Lettering -

Joe Rosen, Gaspar

Saladino (splashpage)

Colouring - Glynis Wein

"The Weapon and the

Warrior!"

(7 pages)

Story -

David Kraft

Pencils - Pablo Marcos

Inks - Pablo Marcos

Lettering -

John Costanza

Colouring - Glynis Wein

|

|

|

| |

| In Thor #252, the God of

Thunder, in search of Odin gone missing, battles it out

with Ulik, "the most savage troll of all!"

as the cover blurb puts it (and who appeared previously

in issues of Thor available in MARVEL MULTI-MAGS). However, readers

only got 11 pages of this confrontation, since this issue

(and the next) contained a backup feature: The famous Tales

of Asgard were back. |

| |

As for the regular Thor stories

of this period, Len Wein summed it up nicely in

2016.

"The

legendary Jack 'King' Kirby had introduced

the magnificent scope and majesty of fabled

Asgard, but John [Buscema] added a power and

grace that was uniquely his own. John had a

way of understanding characters that was

positively supernatural in its depth.

In John's stories,

every pose was unique to the character at

hand, every gesture, every expression. No two

characters would ever sit the same in a John

Buscema story, and nobody could put a figure

in a chair like John. You could feel every

ounce of that character's weight as he or she

sat, feel the weighty matters that stooped

their shoulders." (Wein, 2016)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Pablo Marcos, who moved from his

native Peru first to Mexico and then to the US in the

1970s, was also an established artist with an

accomplished background in illustration and art, but the Tales

of Asgard segment seemingly didn't thrill readers

enough for Marvel to continue the experiment after the

conclusion of this story in Thor #253. |

| |

|

|

Incidentally, the Grand Comics Database states that

Buscema only did the breakdowns

for this issue of Thor and that Tony

DeZuniga provided the finished art.

But regardless of how much Buscema and how much

DeZuniga ended up in the finished product, there

are, as always with issues of Thor from

this period, some truly classic vignettes to be

found and admired.

The cover for Thor #252

can easily be recognized as Jack Kirby's work.

However, and again according to the GCD, Thor's face was reworked

by John Romita & John Verpoorten. It was

understandable in the case of DC, when Kirby

joined them from 1970 to 1975 and his renditions

of Superman didn't conform to the

"established DC visuals", but in this

case Kirby did actually create and shape the

classic 1960s "Thor visuals".

Maybe it was just

another sign that Marvel and Kirby would never

really be happy with each other ever again.

The cover would be

used in 2016 for the frontispiece of the 15th volume of

Thor's adventures in the Masterworks

series.

|

|

| |

|

|

Regular buyers of

MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS would

be able - with a little bit of

luck - to continue reading the

story of Thor and Ulik (as well

as the conclusion to the Tales

of Asgard backup) as

Thor #253 would become available

in a MARVEL MULTI-MAGS the

following month. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

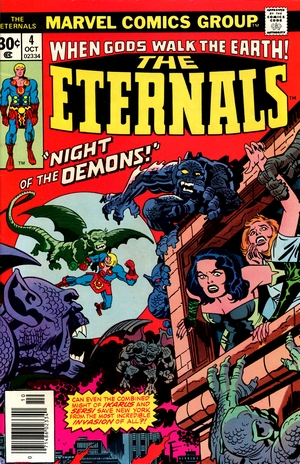

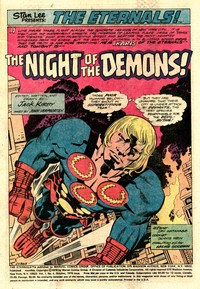

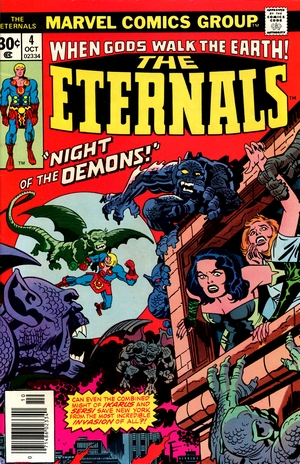

ETERNALS #4

October

1976

(monthly)

On Sale:

13 July 1976

Editor -Jack

Kirby & Archie Goodwin

(consulting)

Cover - Jack Kirby (pencils)

& Frank Giacoia (inks)

"The

Night of the Demons" (17

pages)

Story - Jack

Kirby

Pencils - Jack Kirby

Inks - John Verpoorten

Lettering - Irv Watanabe

Colouring - Glynis Wein

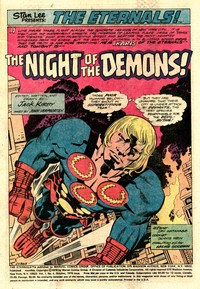

STORY

OVERVIEW

- The

Deviants continue their assault

of Manhattan, enacting Kro's plan

to manipulate Earth's human

population into becoming their

willing servant soldiers through

the great fear that the Deviants

instil in humans who see them as

Devils and Demons. In the course

of this attack, Kro succeeds in

rendering Ikaris unconscious,

though his body is retrieved from

the ocean floor by Ajak, another

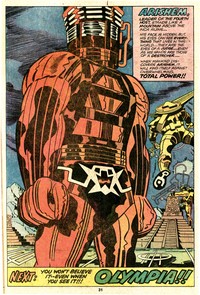

Eternal. Meanwhile, Arishem the

Judge, leader of the Fourth

Celestial Host, continues to

survey the Inca ruins from which

the Celestials were summoned by

the Cosmic Beacon.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Most of the time, the Eternals

were a fun read, though they could be a real mouthful

too. But in order to fully understand the Eternals, one

needs to understand the enormous amount of Jack Kirby's

personal and professional history tied into this title. Kirby left Marvel Comics in 1970 for

DC Comics, increasingly angered by what he perceived to

be an intentional and continuous denial of credit for his

share in creating much of the Marvel Universe. DC

promised him not only full credit but also full artistic

freedom, the result of which was Kirby's "Fourth

World" meta-series, a blend of classic mythology and

science fiction. For some it was the ultimate comic book

saga, while to others it just all seemed too convoluted

and confusing, and the latter group of people seemed to

be in the majority as Kirby's work didn't sell near as

well as DC needed it to. As the number of cancellations

of Fourth World titles grew, so did Kirby's

disappointment with DC, and after his contract ended in

Spring 1975 Jack Kirby once again went to work for

Marvel. In return for this industry scoop, "the

King" essentially just wanted to be left alone to

write and edit his own stories with no co-plotters or

tie-ins with other titles done by other people, keeping

his work deliberately detached from Marvel continuity

(Gartland & Morrow, 2013).

|

| |

| In terms of new concepts, Kirby

started working on The Eternals, which was

thematically similar to his DC work (especially

the New Gods) but actually took its core

inspiration from Swiss author Erich von

Däniken's Chariots of the Gods - in

which the author made the both fascinating and

controversial claim that Earth had been visited

by aliens in the past and that evidence of this

could be found in artefacts and the mythologies

of ancient civilizations. Working

on this premise, Kirby postulates such an alien

visit in our prehistoric past. Through genetic

experimentations these "Celestials"

create three distinct species: Earth's humans,

the "Deviants" (whose genes are so

unstable that every one of them is grotesquely

different and they all have lived on the bottom

of the ocean for centuries), and the

"Eternals" (undying and beautiful

humanoids with superhuman mental gifts).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Kirby pitched the series to Marvel under the title of

The Celestials, but

"Someone at Marvel

felt the new series could piggyback off [von

Däniken's] book's success and changed the title from

The Celestials to Return of the Gods (...) In their

enthusiasm to cash in, Marvel also created a cover

with the new title presented in the same font as the

logo on Däniken's celebrated work. Once someone in

the legal department saw the cover (...) he told

editors "Wait a minute, we're going to get our

rear ends sued off here". The title changed

again, to The Eternals." (Ro, 2004)

|

| |

|

|

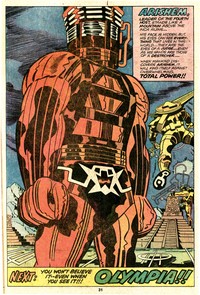

It was once again

a typically high-flying Kirby

concept, accompanied by artwork

of complex machinery, but at

least to start with it seemed to

work well enough. Although of

course a matter of taste, a

certain "looseness"

seemed to plague Kirby's work

since his return from DC. His

plotting would sometimes go off

in more directions than most

readers were willing to accept

let alone care for, and even his

artwork at times showed signs of

coming undone (compare the hands

in these two panels here from Eternals

#4, separated only by a single

page). Ultimately,

his work came across as being too

detached from what the average

reader would expect. And since

Marvel Comics had always been

about finding "the formula

that sells", this became a

problem, aggravated by the fact

that by that time Kirby was

living and working in California

and the Marvel offices were in

New York.

|

Communication

was slow, and it seems

that opinions on Kirby's

work started to drift to

extremes - some still

admired it, while others

simply couldn't stand it

(Gartland & Morrow,

2013). By

the time Eternals

#4 hit the news stands,

Kirby was still building

his cast and plotting out

the general theme, and

the letters page was full

of praise for the first

issue, with readers

rejoicing about his

return to Marvel and

expecting big things.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

For some editors at Marvel, that initial enthusiasm

waned rather quickly.

"In addition to

disliking the dialogue (which was sometimes ludicrous

but always earnest, as in the scene [from Eternals #5]

when an innocent bystander ran through crowded

metropolitan streets yelling "Run! Run! The

Devil's come back from space with an army of

Demons!"), they wanted more renowned Marvel

heroes in the book." (Ro, 2004)

So Kirby tried to appease his

critics by linking the Eternals to the Marvel Universe,

but explaining the presence of the Hulk as an instance of

an android robot (allowing him to still keep things

somewhat apart) only frustrated them more. An increasing

amount of corrections of dialogue made in NYC (with Kirby

only finding out when he saw the printed copies) made the

situation more and more difficult. When Kirby's contract

came up for renewal in April 1978, Stan Lee made it clear

that he only wanted Kirby's artwork and no more of his

scripting (Howe, 2012). Not surprisingly, Kirby left

after only three years at Marvel, went to work for the

animation industry, and never returned to Marvel again.

|

| |

|

It is probably fair to say that

all of Kirby's 1970s work is something of an

acquired taste, but the Eternals are

comparatively accessible and make for

entertaining reading most of the time.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

Copies

of the Eternals

appeared frequently in

MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS, and although

the evidence available at this

point in time continues to

present some holes in the data,

Marvel's MULTI-MAGS may

even have carried a complete and

full run of all 19 issues. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

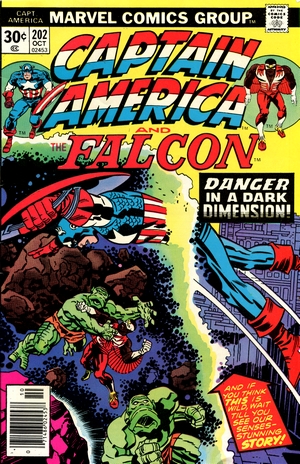

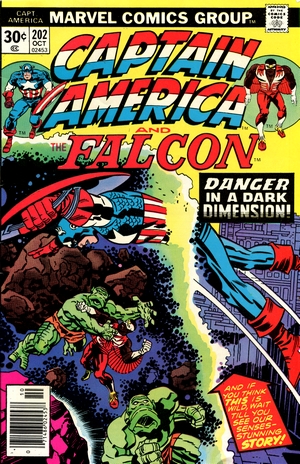

CAPTAIN

AMERICA #202

October

1976

(monthly)

On Sale:

13 July 1976

Editor -Jack

Kirby & Archie Goodwin

(consulting)

Cover - Jack Kirby (pencils)

& Frank Giacoia (inks)

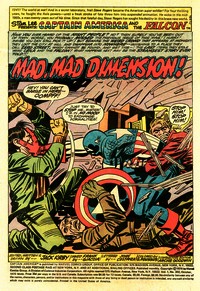

"Mad,

Mad Dimension!" (17

pages)

Story - Jack

Kirby

Pencils - Jack Kirby

Inks - Frank Giacoia

Lettering - John Costanza

Colouring - George Roussos

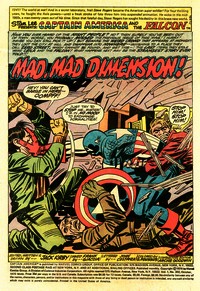

STORY

OVERVIEW

- Falcon

has disappeared, and oil magnate

and altruistic adventurer

"Texas Jack" Marshall

Muldoon believes that it has to

do with "Zero Street" -

which has mysteriously vanished

too, including its asylum and its

most notorious inmate, one Dr.

Abner Doolittle, a nuclear

physicist, who apparently

perfected his dimension machine,

transporting the asylum. Muldoon

is actually spot on, since this

is exactly what happened to

Falcon, who is now battling a

monster in said dimension.

Meanwhile, when a strange

fireball portal appears at what

once was Zero Street, Cap leaps

through it, followed by Texas

Jack...

|

|

|

|

| |

| As mentioned above, when Jack

Kirby returned to Marvel in 1975, he really just wanted

to be left alone to write, draw and edit "his own

thing", and Captain America and the Black Panther

were the only Marvel characters (which of course he had

co-created) that Kirby agreed to return to, but here

also, he deliberately detached them from Marvel

continuity (Gartland & Morrow, 2013). |

| |

Kirby took over

with Captain America #193 and a story

arc entitled Madbomb. The cover sported a blurb

reading "King Kirby is back - greater

than ever!" and the promotional copy

for this issue screamed

"King Kirby

is back to bring you an all new action-packed

issue! "Madbomb" - can it really

destroy the earth? Can Cap and Falc save the

world? Read to find out!"

Madbomb followed on the

heels of an extended run by Steve Englehart, who

had firmly linked Captain America to frequent

political and social commentary. Jack Kirby's

take was an entirely different one, portraying

Steve Rogers as a patriot whose all-out action

was his social commentary, all for the good of

the nation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Kirby conceived this plot as an eight chapter arc,

leading up to the anniversary #200 issue of the title,

which was quite a daring concept back in 1976. And while

the artwork was your essential Kirby - square-jawed faces

and two-fisted action - his plotting just seemed to run

away with him as everything came and went so fast that it

was hard to follow at times. Adding to this the fact that

nothing of what happened in Captain America

seemed to affect the Marvel Universe at all (which was

exactly how Kirby wanted it to be), it all felt

increasingly weird to many Marvel fans (Gartland &

Morrow, 2013). "Madbomb"

was followed by the story arc "Night People",

of which this issue is its second instalment.

|

| |

|

|

Marvel was trying

to sell Kirby's Captain America

as a "startling new

concept" (cover blurb

on Captain America #208), but

more and more negative letters

from readers were received (and

published) which in general

praised his artwork as being

superb but qualified his writing

as appalling (Ro, 2004). Gartland

& Morrow (2013) claim that

this was to a degree fabricated

by people inside Marvel wanting

to bully Kirby out, while Howe

(2012) quotes an unnamed Marvel

staffer who snuck self-penned

positive letters into Kirby's Captain

America issues to try and

counter-balance all the negative

feedback pouring in.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Jim Shooter, who

would become Marvel's

Editor-in-Chief in January 1978,

would later add dismal sales

figures of the title to the

commotion:

"We

had single-digit sales

figures for Captain America,

and at a time the Marvel line

average was up near fifty

percent." (Ro,

2004)

When

Marvel called Kirby to tell him

about the low sales and that he

would have to work with the New

York editorial staff and a

dialogue writer, Kirby (who also

refused to at least have Cap

fight well-known and

fan-favourite villains) replied

that he'd rather leave the book.

Jack

Kirby's run on Cap ended with Captain

America #214 (October 1977),

after which Roy Thomas and George

Tuska took over and practically

rebooted the series with a

complete retelling of Captain

America's origin. It was almost

painfully evident that Marvel

wanted its star-spangled hero

back.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Today,

any MARVEL MULTI-MAGS is a time

capsule; opening this plastic bag

right here offers a nostalgic

glimpse into what it was like to

be a comic book reader in October

1976.

So what else

was going on back then?

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The US

Billboard Chart saw three

number 1s during October

1976: Walter

Murphy and the Big Apple

Band with "A Fifth

of Beethoven" as

well as Chicago with

"If you leave me

now" for one week

each, while Rick Dees and

His Cast of Idiots got

two weeks at the top with

"Disco Duck (Part

1)". In the

UK, ABBA with

"Dancing Queen"

and Pussycat with "Mississippi"

topped the charts for two

weeks each - clearly not

reflecting at all the

fact that 1976 was the

year that Punk Rock

exploded onto the British

music scene. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The New

York Times Bestseller

list for October 1976 was

topped by Leon Uris'

"Trinity", a

spot he occupied since

June; by the end of

October, however, the

number one position would

go to Agatha Christie's

posthumously published

last Miss Marple book,

"Sleeping

Murder".. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In

October 1976 John

Schlesinger's

"Marathon Man"

was the most popular

movie in the US. Overall,

"Rocky" was the

US top-grossing movie

while "Jaws"

(which had been released

in 1975 in the States)

topped the 1976 list in

the UK. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In the

US, all of the three most

popular TV shows came

from ABC, with

"Happy Days"

taking the top spot.

Numbers for the UK are

sketchy, but it appears

that the TV premiere of

James Bond's

"Goldfinger"

got the most viewers to

sit down in front of the

telly. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

FURTHER

READING ON THE THOUGHT

BALLOON |

| |

| |

|

|

"Comic

packs" not only sold well

for more than two decades, they

also offer some interesting

insight into the comic book

industry's history from the 1960s

through to the 1990s. There's

more on their general history here. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

There's more

on the background and the history

of the Marvel Multi Mags here. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

There's more

background information and

discussion of the "yellow

and green on white (3 comics for

89¢)" label MARVEL MULTI-MAGS here. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| |

| |

|

BREVOORT

Tom (2007) "Marvel Multi-Mags", Blah Blah

Blog, originally published online 28 April

2007, reposted 18 April 2020 GARTLAND Mike

& John Morrow (2013) "You can't go home again - Kirby's

1970s return to the "snake pit" of

Marvel Comics",

in Jack Kirby Collector #29

HOWE

Sean (2012) Marvel Comics - The Untold Story,

Harper Collins

RO

Ronin (2004) Tales to Astonish - Jack Kirby,

Stan Lee, and the American Comic Book Revolution,

Bloomsbury

WEIN Len

(2016) "Introduction", Marvel

Masterworks: Thor, Vol. 15

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

(c) 2021-2023

uploaded to the web

11 December 2021

minor corrections 19 August 2023

|

| |

|

| |

|