SYNOPSIS

! SPOILER ALERT !

IRON MAN

Continued from Tales of Suspense

#87, where the Mole Man used a device to

cause the ground beneath the Stark

Industries factory to cave in and the

building to sink into the ground, thus

enabling him to capture an atomic powered

"earth borer"...

Iron Man, who was in one of the now

collapsed buildings, now discovers that

Pepper Potts was also in the factory, and

they both soon find themselves attacked

by the Mole Man's Moloids.

As comic book villains are apt to do,

the Mole Man explains his intentions at

great length, giving Iron Man enough time

and wiggle room to fight off the Moloids.

However, the Mole Man then unleashes a

fire breathing dragon and, while Iron Man

fights off this beast, kidnaps Pepper and

takes her back to the boring device.

When Iron Man (having defeated the

creature) catches up with them again, the

Mole Man orders him to show him how the

boring device works in exchange for

Peppers life. Iron Man uses a ruse and

actually instructs the Mole Man how to

cause the device to overload and explode,

escaping with Pepper just before all is

blown up, seemingly killing the Mole Man

in the process.

SYNOPSIS

! SPOILER ALERT !

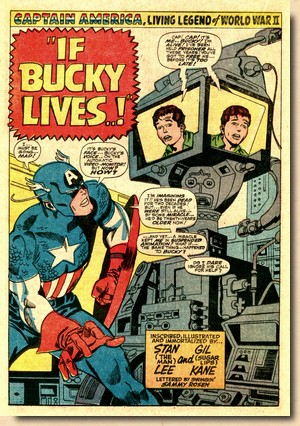

CAPTAIN AMERICA

At Avengers Mansion, Captain America

receives a distress call from somebody

who appears to be Bucky, telling him that

he's been a prisoner for all these years

on a remote island. Cap races off to the

rescue of his trusted WWII sidekick, not

knowing that he is being lured straight

into a trap, with the Swordsman and Power

Man having been recruited to face off

against Captain America upon his

arrival...

When Captain America arrives on the

remote island he quickly realizes that in

order to save Bucky's life he first has

to battle it out with both costumed

villains. He defeats both of them easily

but then finds himself trapped in what

seems to be an indestructible transparent

bubble.

As Cap is struggling but essentially

helpless, the villain who employed the

Swordsman and Powerman reveals himself.

The story continues on from this

cliffhanger in the next issue, where

readers will learn that it is the Red

Skull who has trapped Captain America...

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

REVIEW

& ANALYSIS

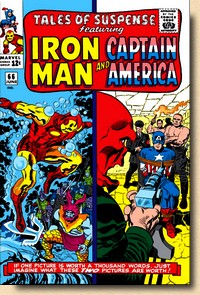

In 1966, Tales of Suspense was

one of Marvel's so-called two-feature

titles - a comic book essentially shared by two

different starring characters in their own stories. They

were a staple of Marvel Comics for several years

throughout the 1960s, but the format wasn't the result of

a voluntary decision.

|

| |

|

|

The need

to split one comic book between two main

characters actually had its roots back in

1957, when Martin Goodman's new choice of

distributing company for his comics,

American News Company, went out of

business unexpectedly. The fallout for

Goodman and his Atlas Comics was that

they found themselves with no other

choice than to switch to Independent News

as distributor. The snag: unlike what the

name suggested, Independent was in fact

owned by National Periodical - who also

happened to own Goodman's rivals DC

Comics. The

well-known outcome of this was that Atlas

and then Marvel Comics was limited by

contract to a monthly publishing output

of eight titles only (Cooke, 1998). As

a result, Stan Lee juggled with a mix of

bi-monthlies, cancelling Romance and

Western titles, and turning Horror books

into Superhero titles - all in order to

get the distribution slots freed up for

what was selling: Marvel Comics' brand

new and different approach to the genre

featuring "superheroes in the real

world".

Once the old Atlas horror and mystery

titles had been given over to Marvel's

new superheroes (albeit retaining their

original titles), yet another way of

approaching the limited distribution

problem was the two-feature title.

This formula had already been

successfully tested since Strange

Tales #110 (July 1963) when Doctor

Strange joined the Human Torch (who would

later be replaced with Nick Fury as of

issue #135, August 1965). In late 1964 Tales

to Astonish became a split book too,

with issue #60 (October 1964) featuring

the Hulk and the previous solo star

character Giant-Man (replaced by Namor

the Sub-Mariner as of issue #70) in

separate stories. Iron Man followed suit

and began to share his Tales of

Suspense a month later with Captain

America (issue #59, November 1964).

Marvel Comics finally

broke free from the distribution

constraints in 1967 when Independent was

purchased by Kinney National Company and

they got a new deal. The result was an

explosion of new titles as established

characters finally could be given their

own comic book - Tales

of Suspense, Tales to Astonish and

Strange Tales alone split to become

six titles instead of three.

By the time Tales of Suspense

#88 hit the newsagent stands the Iron Man

and Captain America double-bill was well

established, and the two superheroes took

turns for cover appearances (after the

two-feature titles dropped the initial

"split-cover formula" as seen

above with Tales of Suspense

#66.

|

|

|

| |

| This would last until Tales of Suspense #99

(March 1968), as the two heroes got their own titles

after that - Iron Man went on to feature in Iron Man

& Sub-Mariner #1 and then a month later in Iron

Man #1, whereas Cap took the numbering with him and

started out in Captain America #100. Iron Man

would always come first (Tales of Suspense was,

after all, "his" original title), and in this

issue his story starts out with a classic Gene

Colan splashpage, highlighting the underlying

vulnerability of Marvel's superheroes. The unfolding

events (still plotted by Stan Lee himself at the time)

feature more of Colan's breathtakingly dynamic and

cinematographic artwork, which worked well with Frank

Giacoia's inks. Two masters at work.

|

| |

|

| |

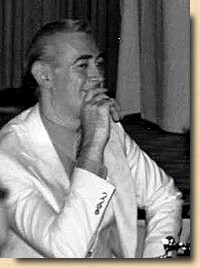

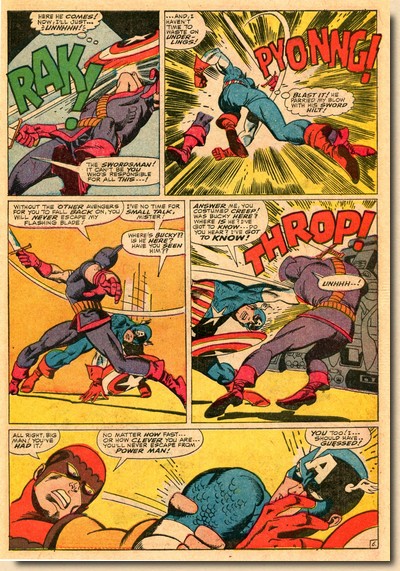

| The following Captain America story, again scripted

by Stan Lee, was pencilled by another industry great: Gil

Kane. Born Eli Katz in 1926 in Riga, Latvia, he emigrated

to the US with his family in 1929 and grew up in

Brooklyn, where he developed an early interest in comic

books and landed his first job with MLJ (later Archie)

Comics in 1942. At the age of only 16, he left school in

order to be able to continue what had started out as a

summer job (Groth, 1996). He used the name "Gil

Kane" to sign his first inking work in MLJ's Zip

Comics #14 (May 1941) and subsequently stuck with it. |

| |

Gil Kane

(1926 - 2000)

|

|

His first work

for what would later become

Marvel Comics featured in Young

Allies #11 (March 1944),

followed by uncredited ghost

artist work for Jack Kirby in

DC's Adventure Comics #91

(May 1944). Following highly

influential work for DC in the

Silver Age superhero revival

(e.g. Green Lantern), Kane also

worked on a number of Marvel

titles in the 1960s. He would

eventually not only become the

regular penciller for The

Amazing Spider-Man in the

early 1970s, but also Marvel's

preeminent cover artist

throughout that decade.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Gil Kane is especially remembered for his gripping

rendering of the story arc depicting the deaths of both

Gwen Stacy and the Green Goblin (Amazing Spider-Man

#121–122, June–July 1973). At that time,

sacrificing two high profile characters without a back

door to bring them back to life was highly unusual

(comparable really to Hitchcock shocking moviegoers in

1960 with the violent death of his female leading actress

Janet Leigh after only 47 minutes into Psycho),

and Kane's pencils suited the dramatic events well. His

artwork can truly be labelled classic mid-1960s to late

1970s and embodies what most comic book fans of that era

would describe as the kind of artwork that typifies what

they liked about comic book art: a dynamic approch to the

action of the story and a clear focus on the characters

involved (which could sometimes result in simple or no

backgrounds at all, as illustrated by the panels from Tales

of Suspense #88 shown here). |

| |

House

of Mystery #180 (June 1969)

|

|

Gerry Conway (who

scripted the famous Amazing

Spider-Man #121–122 issues)

described Kane as "a marvelous

draftsman and an idiosyncratic

storyteller" while also noting

that unless given a tighter plot (which

Kane himself preferred) his work "could

sometimes result in lopsided

storytelling; the first two-thirds of a

story would be leisurely paced, and the

last third would be hellbent-for-leather

as Gil tried to make up for loose

storytelling". (Conway in

Buchanan, 2009). It just goes to show

that comic books are always a team

effort. With writer Roy Thomas, Kane

helped revise Marvel's Captain, revamped

a preexisting character as Adam Warlock,

and co-created martial arts superhero

Iron Fist as well as Morbius the Living

Vampire.

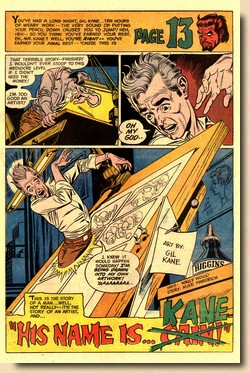

Gil Kane is also remembered for one of

the most extraordinary cameos in comic

book history, being made the lead

character in writer Mike Friedrich's

story "His Name Is... Kane" in

DC's' House of Mystery #180 (June

1969). In this six-and-a-half-page tale,

pencilled by Kane himself, frustrated

comic-book artist Gil Kane kills his House

of Mystery editor, Joe Orlando - but

Orlando, himself an artist, then goes on

to enact revenge by drawing Kane into

artwork that is then framed and mounted

in the house, thus trapping him there.

Kane remained active as an artist,

also illustrating paperback novel and

record album covers, until his death in

January 2000.

|

|

|

| |

| |

LIFE'S

A SWINGIN' SYMPHONY - 'NUFF SAID!

|

| |

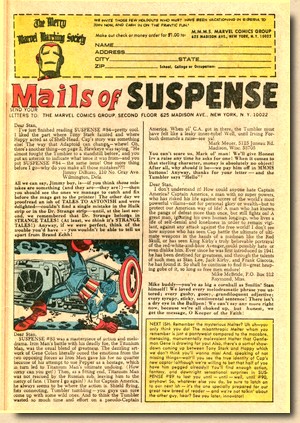

| An absolutely integral part of being a Marvel Comics

reader and fan in the 1960s and 1970s were the letters

pages (aptly titled "Mails of Suspense" in this

case) and the monthly Bullpen Bulletin. |

| |

These were the gathering

points for all "true

believers", where opinions amongst

readers as well as informations from the

House of Ideas as well as directly by

Stan the Man himself were handed out, and

they made you feel that you were a part

of something special - and sometimes fans

would check out these pages even before

reading the actual story material in the

comic book they were holding.

"As

a mad Marvelite, you're more than

just a reader - you're a friend! So

drop me a line soon as you can, I'll

be waiting, hear?" (Lee,

1972)

It was, of course, all by design, and

one of the major elements which so

successfully set Marvel apart from DC.

"What

I always tried to do with Marvel was

to make it seem like a club, like an

inner group that we knew about and

the outside world wasn't even aware

of. If you read Marvel you were on

the inside, you were hip, and it was

sort of an exclusive thing, limited

just to Marvel readers. And I tried

to talk to the readers as if they

were friends, not readers, so that

not only - hopefully - did they enjoy

the stories, but they enjoyed being

part of the Marvel mystique if you

might say, and I'm probably making it

sound much more profound than it

really was, but that's the way I

looked at it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I wanted

people to be aware of Marvel, and I

wanted people to know about the

mysticism and the magic and

marvelness of Marvel, and they say

that if you build a better mousetrap

the world will beat a path to your

door, but the world will only do that

if it knows the mousetrap exists, and

I didn't want us to be doing these

books in a vacuum, because you know

comic books had no advertising

budget, no promotion. There were no

ads on television, on the radio, in

newspapers - you just printed your

comic book and it was out there, and

I was sort of like Joan of Arc, I was

on a crusade, a mission, to let the

world know about the marvelous world

of Marvel. So in that sense, I guess

I was a little bit of a

huckster." (NN, 2003)

The

"mysticism

and magic and marvelness" of Marvel

was of course echoed (as always somewhat

tongue-in-cheek) by the famous

alliterations Stan came up with as titles

for the monthly Bullpen Bulletins.

These initially started out as part of

the two-page letters section of Fantastic

Four, which often concluded with a

"Special Announcements Section"

where Stan Lee responded to more general

letters and promoted other Marvel titles.

A vital element - "The Mighty Marvel

Checklist" - appeared for the first

time in this Special Announcements

Section in Fantastic Four #33

(December 1964). A separate "Merry

Marvel Bullpen Page" appeared in

comics cover-dated July and August 1965

(with the checklist and special

announcements still on the letters

pages), and the first stand-alone

"Marvel Bullpen Bulletins"

page, complete with checklist and special

announcements, finally made its debut in

the issues cover-dated December 1965.

|

|

|

| |

The Bullpen Bulletin was thus still a fairly new

concept to readers of Tales of Suspense #88, and

"Stan's Soapbox" - another pivotal element of

Marvel's editorial page - was still more than a year out,

first appearing in the June 1967 issues. In the April

1966 Bullpen Bulletin, Stan touched on Marvel's TV shows

going international, Gene Colan's mishaps with his new

motorcycle as well as medical problems suffered by Larry

Lieber and Bill Everett (after all you want to know

what's going on with your friends), complete with a

little sting directed at Brand Echh (i.e. DC Comics)

suggesting they were into voodoo to hamper Marvel's

bullpen of creators, and more personal news concerning

the hiring of John Verpoorten, Roy Thomas forsaking

University for Marvel Comics, and Jack Kirby being fellow

artists' choice for best artist (or, as Lee would put it

in his self-caricaturing way, "pencil pusher").

Stan Lee wrapped it all up with one of his typically

upbeat and avuncular messages to readers:

"We're plumb outta room, so hang loose

and face front! Life's a swingin' symphony, and we

don't wantcha to miss a note of it! 'Nuff said!"

|

| |

| |

FACTS

& TRIVIA

|

| |

| Tales Of Suspense #88

went on sale in the US on 1 October 1966 and was also

made available roughly three months later to the UK

market with a pence price variant cover. |

| |

|

|

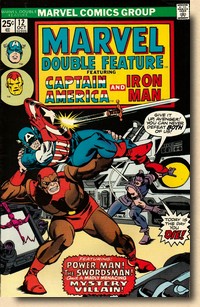

The Captain America story

was reprinted in Marvel Double

Feature #12 (October 1975), a Marvel

reprint title focussed on Tales

Of Suspense, together with the Gil

Kane cover. Typical for Marvel's

mid-1970s reprint titels, the Cap story

lost 2 pages and the cover received some

alterations to the colouring (actually

making it more consistent with the

colouring of Power Man's suit in the

actual story). Somewhat confusingly,

however, the Iron Man story had already

been reprinted (again leaving out two

pages) in Marvel

Double Feature #5 (August 1974); the

Iron Man story featured in Marvel

Double Feature #12 was taken from Tales

of Suspense #95 (November 1967).

While the cover has been

reprinted multiple times in Marvel's

various collected editions (Essentials,

Masterworks, Omnibus editions), it was

also used by international publishers.

Italian Editore Corno did

so no less than twice, for their Capitan

America #11 (1973) and Capitan

America Gigante #5 (1980). Mexican

publishers La Prensa adorned their Capitán

América #3 (1968) with Kane's

wonderful cover, as did Panini España

for their Marvel Gold: Capitán

América #1 (2011).

|

|

|

| |

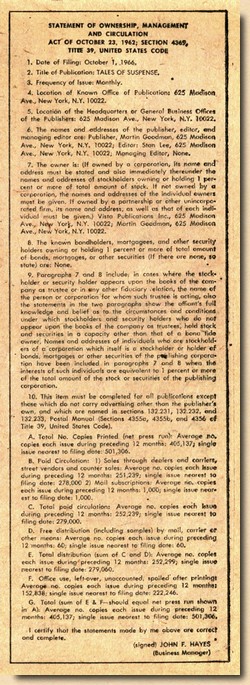

| Although many readers at the time probably had little

to no interest in the small print Statement of

Ownership, Management, and Circulation which appeared

once every 12 months in the pages of their comic books,

they provide us with some interesting statistics

regarding print runs, actual sales, and subscription

numbers. Tales Of Suspense #88 contains

such a Statement. These had been required of publishers

who shipped their printed matters Second Class since the

19th Century, but as of

1960 they were also required to list their average paid

circulation for the past twelve months. |

| |

|

|

Printed sideways (so that if you

wanted to read it you had to turn your comic book

around 90 degrees) and in the smallest possible

of fonts, the Statement contained in Tales Of

Suspense #88 tells us that the title had an

average print run of 405,137 copies during the

preceding 12 months (although the issue nearest

to the filing date had a print run of 501,306

copies). Of this average print run of 405,137

copies during the preceding 12 months, 251,239

copies had been sold through dealers, carriers,

street vendors and counter sales; 1,000 copies

had been sold through subscriptions. This

averaged a total paid circulation of 252,299

copies (up to 279,060 copies for the issue

nearest to the filing date) - which left an

average of 152,838 copies counted as "left

over, unaccounted, spoiled after printing".

That's a whopping 38% of the entire print run not

generating revenue, but actually still a lot

better in comparison to later years when this

figure could even go up and above 50%. The

traditional distribution channels for comic books

were increasingly fraught with problems and would

ultimately prove to become untenable, leading

into the so-called direct market.

My personal copy of Tales Of Suspense #88

also illustrates another aspect of comic books at

the time: the care taken to produce this cheap

product at the printers could sometimes be

lacking, and in this case the stapling is way off

the centre line of the folded pagesheet. Such

copies would later on not grade highly and would

become popular items to have an artist involved

sign at conventions (witness Gil Kane's signature

on this specific copy) in order to raise its

value.

|

|

|

|

| |

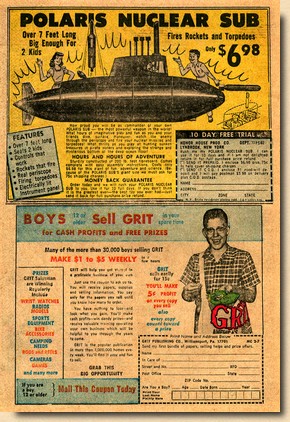

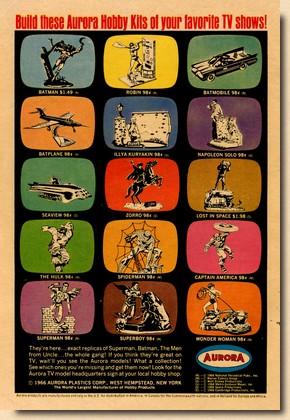

| No 1960's (and 1970s) Marvel comic book was, of

course, without third party advertising, some of which

was "okay" (mostly if it featured Marvel

characters) and some of which was, well, something else

(such as the infamous flea market ads promising anything

and everything). Tales Of Suspense #88 really

featured it all. Very noticeable is the amount of ads

promising "from home training" in all kinds of

trades, along with a full page ad offering a "second

chance for High School dropouts to get diplomas".

Are we therefore to assume that the Academy of Home

Study assumed that a substantial number of their

target customer base was to be found amongst comic book

readers? Not really, since their advertising campaigns in

the late 1960s and early 1970s could be found up and down

in newspaper ads and even on matchboxes. Somewhat more

interesting, at least to younger and teenage readers,

were those sellers pushing items with outrageous

promises. Those of us who had their doubts even back then

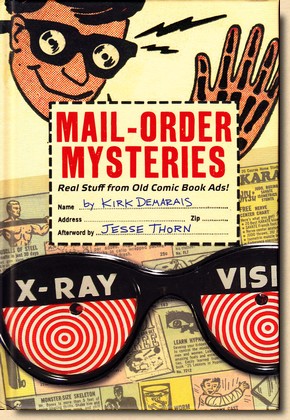

will find Kirk Demarais' 2011 book Mail Order

Mysteries - Real Stuff from Old Comic Book Ads! highly

amusing. Listing and illustrating more than 150 "extraordinary,

peculiar and downright fraudulent collectibles whose

promises have haunted comic book fans for decades",

the actual items offered in these fabled ads were a let

down every time.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

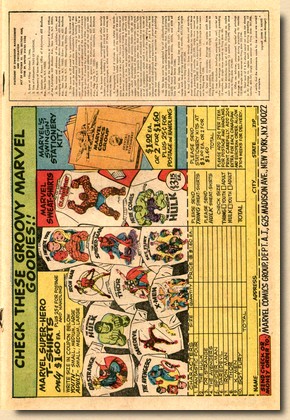

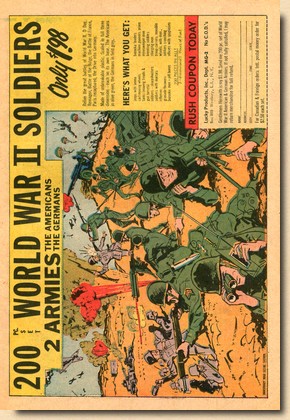

| A classic example are the "200 soldiers

sets" (also advertised in Tales Of Suspense #88):

the box turned out to be the cheapest cardboard you could

imagine, and the soldiers were absolutely flat (i.e.

almost two dimensional) and all in the same pose (as

described and illustrated by Demarais). Still, there are

some ads of interest, such as the Electronic Computer

Brain - remember, the year is 1966. On the whole,

however, readers considered ads a nuisance unless they

were in-house plugs for other titles (merchandising was

gradually taking off, but still in its infancy). |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY BUCHANAN

Bruce (2009) "Morbius the Living

Vampire", in Back Issue! #36

(October 2009)

COOKE Jon B. (1998) "Stan

the Man & Roy the Boy: A Conversation Between Stan

Lee and Roy Thomas", in Comic Book Artist #2,

Summer 1998

DEMARAIS Kirk (2011) Mail Order

Mysteries - Real Stuff from Old Comic Book Ads!,

Insight Editions

GRATH Gary

(1996) "Interview with Gil Kane, Part I", in Comics Journal #186

(April 1996)

LEE Stan (1972) "A special message from Stan Lee",

editorial published in UK Mighty World of Marvel #1

(30 September 1972)

NN

(2003) "Stan Lee Interview", contained as extra

feature on the double disk DVD release of the movie Daredevil

(personal transcript)

|

| |

| |

The

illustrations presented here are

copyright material.

Their reproduction for the review and

research purposes of this website is

considered fair use

as set out by the Copyright Act of 1976,

17 U.S.C. par. 107.

(c) 2021

|

|

|

|