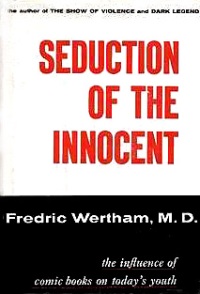

| So although Fredric Wertham was

clearly not the first to demand that "parents

and teachers throughout America must band together to

break the `comic' magazine" (Chicago

Daily News, 8 May 1940), he was undoubtedly the most

influential individual of the American anti-comics

movement. Born in 1895 as Friedrich Ignaz Wertheimer in Nuremberg, Germany, he received a medical degree in 1921 from the University of Würzburg and began his professional life in Munich at the German Research Institute for Psychiatry before moving to the United States in 1922 to work at Johns Hopkins University’s Phipps Psychiatric Clinic (Womack, 1992). Taking the anglicised name of Fredric Wertham he received US citizenship in 1927 and moved to New York City in 1932 where he worked at the Bellevue Hospital Center and its well known psychiatric facilities. Appointed director of the Bellevue Mental Hygiene Clinic in 1936, Wertham also worked as forensic psychiatrist for the city's Department of Hospitals. |

|

| In this

capacity he was called upon to provide psychiatric

examinations in conjunction with criminal court

cases, and in this context Wertham came into

increasing contact with troubled youth. He started to

develop a clinical interest in popular culture, and

his focus began to zoom in on what he perceived to be

the negative influences of movies, radio plays and

comic books. Following his appointment as director of

the psychiatric services at the Queen's Hospital

Center in 1940, Wertham began to write and publish

about what he perceived to be a connection between

popular culture and juvenile delinquency until

deciding to take a markedly more active stance as of

early 1948 when he initiated a symposium on

The

Psychopathology of Comic Books in New York City

by the Association for the Advancement of

Psychotherapy. It was here that he took center stage

for the first time, chairing the event and declaring

it to be a milestone by gathering several speakers

who were presented as specialists on the topic of

comic books - although this appraisal was, from a

non-partisan point of view, somewhat questionable. The symposium marked the beginning of Fredric Wertham's active involvement in the anti-comics movement, which would ultimately lead him to the publication of his best known work, The Seduction of the Innocent, in 1954. Whilst the drive to censor comic books or drive them clean off the market had a long standing by the time he joined the cause, it had been an uncoordinated series of individual statements and events which failed to make more than a short and at best regional impact before Wertham's involvement, which instantly gave the movement what it needed most: a strong leading hand and a powerful aura of perceived professional respect and moral integrity. |

|

Fredric Wertham was the ideal

individual to become the personified anti-comics

icon, simply because he combined all the required

qualtities for success in his personality. His

political standing (which was far more to the left

than the many portraits which describe him as a

liberal make it appear to be) did not contradict an

elitist notion (in this case regarding culture) which

in turn gave rise to a personal belief of holding a

position of absolute insight and truth. These

qualities made him a highly effective populist who

also understood how to use the media, but the most

important element was Wertham's professional

standing, which gave him a mainstream credibility and

a broad acceptance by the media and audiences alike. Not surprisingly, neither the industry nor comic book enthusiasts had any nice things to say about Wertham, and to the growing comic book fandom movement of the early 1960s he became an almost mythical evil beast - the man who had tried to kill the American comic book. |

| It is

therefore quite ironic that Fredric Wertham, a

forensic and clinical psychiatrist, would be all but

forgotten today had he not chosen to become the

leading figure of the American anti comic book

movement of the late 1940s and 1950s. The

effectiveness of his activities in this domain was

such that a lasting wave of contempt from the comic

book enthusiasts' community has ensured that the

memory of his name and his work lives on until this

day. However, the concussions caused by his writings and his speeches were highly damaging to the comic book publishers long before The Seduction of the Innocent and the 1954 Senate hearings. For the industry, he was the personified anti-comics movement icon as early as 1949, when publishers such as Timely/Marvel ran editorials explicitly directed against Fredric Wertham. |

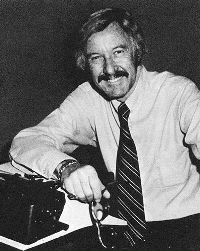

| STAN LEE - SPIRITUS RECTOR OF THE AMERICAN COMIC BOOK RENAISSANCE |

| Stanley Martin Lieber - better known, of course, as Stan Lee - is to comic books and the industry what Fredric Wertham was to the anti-comics movement: the personification of just about everything iconic associated with their fields of activity. Just like Wertham, Stan "the Man" left his public mark to the extent that even people who know little about comics know his name - now set in front of a background of numerous movie adaptations with which, again, Stan Lee is closely associated (although not as much in terms of production as through his numerous cameos). No other comic book writer, editor and publisher even comes close to the imposing shadow cast by this giant of the industry who has grown - again, similar to Wertham - to almost mythical proportions. |

| In a certain sense, Stan Lee (born in New York City on 28 December 1922) and Fredric Wertham were professional contemporaries. Lee entered the comic book industry at the age of just under 17 as an assistant at Timely Comics (published by Martin Goodman, who was married to a cousin of Lee) and then moved on to writing tasks, co-creating his first superhero (the Destroyer) for Mystic Comics #6 in August 1941. A dispute later on that same year between publisher Goodman and the editorial and creative team of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby resulted in Simon and Kirby walking out at Timely and Stan Lee being installed as interim editor. Lee rose to the occasion, displayed an obvious talent and enthusiasm, and was duly promoted to the position of editor-in-chief and art director of the comic book division of Goodman's publishing company. By the time Fredric Wertham stepped up onto the stage in 1948, Stan Lee had thus successfully been in the comic book business for almost ten years. |

|

| The

notion of contemporaries, however, only relates to

both Wertham and Lee being on the playing field at

the same time. In terms of status, they were players

from two entirely different leagues. Stan Lee was

established, respected and generally well-liked at

Timely Comics, but he was still far from being a

public figure, let alone a household name. In

essence, Lee was an industry insider unknown to the

general public. Fredric Wertham, on the other hand,

had virtually exploded onto the scene in no time and

quickly featured in well-known, high circulation

publications such as Collier's, The

Saturday Review of Literature and Reader's

Digest. When Stan Lee finally did come to acquire a similar amount of general public attention and profile in the late 1960s to early 1970s - touring campuses and giving public talks - the active days of Fredric Wertham were all but over. |

According

to Raphael & Spurgeon (2003) it is more likely

that Lee may have been involved in some discussions

with individuals sharing Wertham's views, and that

both his position and his options at the time - from

1948 to 1954 - were of a far more passive nature:

But even if Lee's head to head discussion with Wertham on comic books should be a fictional part of the Stan Lee mythology, it is not entirely outside factual reality, simply because such a discussion did indeed take place in April 1953 - in the pages of Atlas Comics' Suspense #29. |

| WHAT IF... FREDRIC WERTHAM STORMED STAN LEE'S OFFICE? |

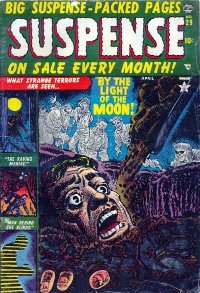

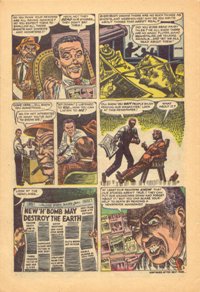

| Atlas Comics (as Timely Comics had rebranded itself in November 1951) published a whole range of comics which featured Suspense in their title one way or the other, and one was simply called just that - Suspense. It was a typical representative of the Atlas line of horror and sci-fi titles, featuring several (usually five) four- to six-page short stories per issue. |

| In the case of Suspense

#29 (April 1953) these were "The Man behind the

Blinds" (6 pages, script by Stan Lee, art by

Fred Kida), "By the Light of the Moon" (5

pages, no credits given), "Strong as an Ox"

(5 pages, script by Stan Lee, art by Jerry Robinson),

"The raving Maniac" (4 pages, script by

Stan Lee, art by Joe Maneely), and "The Man who

was going to destroy America" (4 pages, no

credits given). Although highly run-of-the-mill

routine in terms of its content, Suspense

was a special title in editorial terms as it served

as a testing ground for Stan Lee who made his first

steps towards an editorial approach which would

become his trademark in years to come as he

introduced a letter page - aptly titled Suspense

Sanctuary - and added editorial comments which

already display many traits of his future 1960s/70s

Marvel "bullpen bulletins". Far from being

the inventor of such an editorial approach which

tries to build up a line of communication with its

readership, both the letters page and the editorials

in Suspense very much served the purpose of

giving Atlas a copycat title of EC's popular horror

titles at the time. Suspense #29, on sale in January 1953, was also special in that it was the last issue to be published before the title was cancelled. |

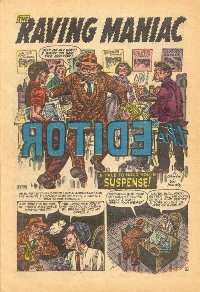

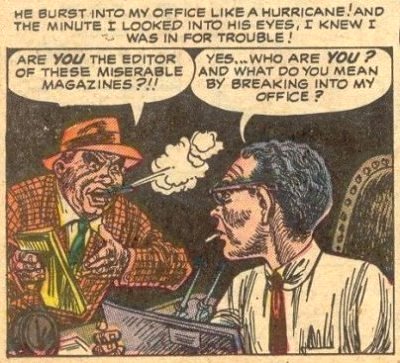

| It is therefore possible to assume that this gave a singular extra dose of editorial liberty, as nothing you could do would endanger the title as it was already doomed in any case (just as would be the case in August 1962, when Amazing Fantasy #15 was the last issue of its title and could thus provide a no-risk opportunity for the tryout of a character called Spider-Man). Whatever the exact circumstances - which appear to be clouded by the mists of comic book history - Stan Lee penned an exceptional 4-page story for the last issue of Suspense called "The Raving Maniac" - illustrated by Joe Maneely - which completely defies the standard plot mould for any horror comic book as he lays out the story of himself as the editor of a comic book company who has to face an enraged person who storms into his office to complain furiously about the terrible content of the publisher's horror comics. |

| Typical

for the approach Stan Lee took to comic book

storytelling in the 1960s, "The Raving

Madman" is an early example of his way of

playing with the internal, plot level reality, and

the external, real world level reality of the reader,

and having them interact at times in a Luigi

Pirandello style. The Italian playwright (1867-1936)

who received the 1934 nobel prize in literature often

played with the so-called "fourth wall",

i.e. the front of the stage which separates a play

from the audience also in terms of their unconnected

realities. He carried this theme to an extreme in his

1921 play Sei personaggi in cerca d'autore [Six

Characters in Search of An Author], where the

stage actually becomes an extension of the real world

reality in which actors and audience both find

themselves, and are thus both part of the setting of

the play. Taken up by other authors and filmmakers

(e.g. Woody Allen in his 1985 Purple Rose of

Cairo, where a fictional film character leaves

his movie and enters the real world), this narrative

motif also plays an important part in the work of

Stan Lee. Lee's pronounced inclination towards a Pirandellian interconnection between the fictional worlds and characters he and others created and these very same real life individuals lead to a number of "self-portrait appearances" - and an actual paradigm according to which the "Marvel Universe" was a factual part of the real world. Stan Lee wrote his first story featuring himself ("The Nightmare") for Astonishing #4 (June 1951), and true to life, he was the editor who was looking for a story for a special edition of - Astonishing. Whilst many other comic book creators would later also include cameo appearances and Will Eisner seemingly was the first to ever do so (in The Spirit strip for 8 June 1947), Stan Lee must rank as the comic book industry's equivalent to Alfred Hitchcock in this respect. Unlike his first self-portaryal, Lee never even touches upon the standard lore of horror and fantasy in "The Raving Maniac" as the story takes place in broad daylight and is completely devoid of anything supernatural. Right from its first panel, the plot jumps to the meta level of the comic book itself as the story unfolds entirely in the offices of a comic book publisher whose output obviously includes a whole range of horror comic books. "The Raving Maniac" thus immediately breaks up the barrier between the fiction of the author and the real world of the readers. This highly unusual narrative for a comic book of the early 1950s is in stark contrast to the conventionality of its visual breakdown as drawn by Joe Maneely, who used a basic six panels in three rows per page layout with only very little variation: the splash page features a double-height double-width introductory panel with the title text line, and two panels are split in half vertically. |

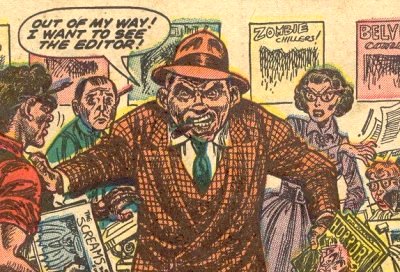

| The story opens with a large splash panel showing an obviously infuriated middle-aged and cigare-chewing man about to storm through the door to the office of an editor, as the inverse writing on what must obviously be a glass panel in a door indicates to the reader. This was a nice and almost cinematographic visual take by Joe Maneely to set the scene in one single shot, an ability which was one of the main reasons why he was one of Stan Lee's favourite go to artists of the 1950s decade at Atlas before this fruitful team-work was abruptly halted when Maneely fell victim to a fatal accident in June 1958, aged 32. |

| The opening shot also clarifies

that the editorial office out of which the reader is

seeing the scene belongs to a comic book publisher

whose mainstay seems to consist of titles such as ARGH

Comics, Zombie Chillers, Casket

Comics (a "casket" being the North

American equivalent to an English "coffin")

and Horror (which is the title of one of the

comic books the enraged gent is about to carry into

the editor's office), and an artist who is pushed

aside by the "raving maniac" carries some

interior pages to a story entitled "The

Screams". One title published by this company of which a cover is seen to be hanging on the wall, however, seems slightly cryptic at first glance - Belvue Comics. |

|

| This is

most probably intended to affirm the notion of those

who have some background knowledge that this whole

story is set in the context of the anti-comics

movement and one specififc indivdiual: Fredric

Wertham, MD - who had been the director of the Mental

Hygiene Clinic at the Bellevue Hospital

Center in New York City. This little background hint right in the very first panel also forms a narrative link to the outcome of the story, where the "raving maniac" is apprehended and escorted away by two individuals clad in white hospital gear. It is obvious that their destination will be a psychiatric ward, and given the New York City base of Atlas and Stan Lee, it is clear that this will conjure up the name "Bellevue" for many readers, as the Bellevue Hospital Center (the oldest public hospital in the US, founded in 1736 and located on First Avenue) is mostly referred to by the general public simply as "Bellevue" and as such most always refers to the hospital's psychiatric facilities. Throughout the entire story there is no explicit reference to the furious visitor being Fredric Wertham, but many clues exist to deduct that Stan Lee was in fact thinking exactly of Wertham and trying to make this implicitly clear, although he came very close to outright confirming this interpretation in an interview. |

|

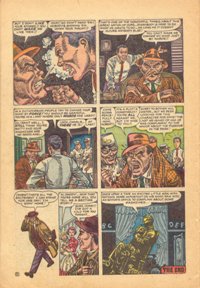

Although thus officially only portrayed as a Wertham clone, the raving maniac displays a whole number of traits easily associated with Wertham. |

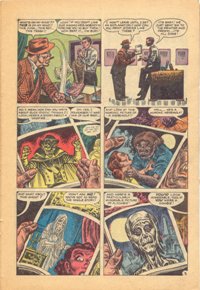

The

raving maniac is portrayed as an individual with an

almost feverish forward driving force - "Out

of my way!" are his first words as he

pushes away an artist standing between him and the

door to the editor's office, and this commanding

style of communication will be the mould for all of

his utterings throughout the story - a style which

matches Wertham's general rhetoric very well.

And just as Wertham stormed various public and media fora in 1948, the raving maniac "burst into my office like a hurricane!". In an angry eruption, he then tells the editor to his face that he finds his publications to be "miserable magazines", "this junk - this rot - this trash!!" - or, in the words of Fredric Wertham MD:

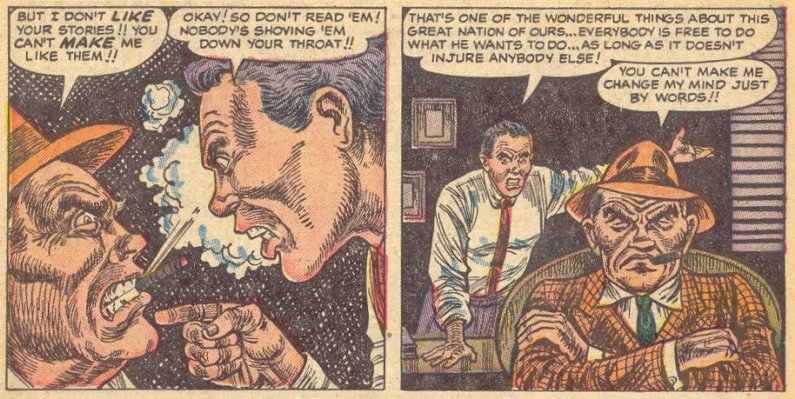

Stan Lee has the editor, a.k.a. himself, counter the ranting of the Wertham Doppelgänger by pointing out that it's purely fiction for fun and relaxation, and that no one is forcing anybody to read these comic books if they don't want to. The position of the "raving maniac" is displayed as a stubborn insistence on his purely personal view, and a perspective that the editor and his comic books should have to conform to the critic's way of seeing things. |

|

Lee, in the persona opf the

editor, thus reiterates two of the main

characteristics of Wertham's position which also

provoked some criticism from other academics.

And even the argument brought forward by the editor confronting this infuriated visitor that the contents of his comic books are simply there to entertain readers in a thrilling way and that the readers know very well how to handle imaginary tales because they are accustomed to these ever since hearing their first fairy tales echoed real-life statements in public.

|

In the words of Stan Lee as the

editor:

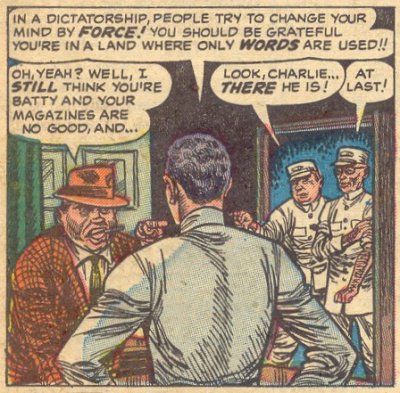

Finally, the editor then strikes his hardest blow by pointing out that

It is at this point in the story that the denouement takes place - the unraveling of the plot enters the stage in the form of the two aforementioned gentlemen from a psychiatric ward who are more than relieved to finally apprehend their eloped patient. |

|

To the

startled editor, one of the wardens explains that "we

been looking for this character for days!"

whilst his colleague adresses their patient:

No family name is mentioned, and this seems fairly in line with set cliches of the era that a psychiatric warden would be addressing his patients by using their first name only. It also seems likely to assume that Stan Lee would not have dared to pinpoint Wertham directly as being the "raving maniac" of this story, given the allusions to the somewhat anti-democratic ideas and the mental health issues of the character. However, choosing the first name Hubert may be considered a step in that direction: the name is of a distinctly German origin (just as Wertham himself was) and, according to US census data, not a particularly common one in the US and thus not amongst the 500 most popular first names for babies in the 1950s. Given Stan Lee's modus operandi, it is highly unlikely that the name Hubert was not chosen deliberately, rather than having a "Mr Smith" or "John", and Lee's ways with words might even justify taking the alliteration of hubERT and wERTham as being no coincidence at all. |

|

It is therefore highly likely

that Stan Lee did, indeed, meet Fredric Wertham - in

a story he wrote. The narrative twist of having him

be an inmate of a psychiatric institution rather than

Wertham's real life position as a psychiatrist surely

offered a certain amount of tongue in cheek

satisfaction to the author, and a fleeting

possibility of getting back at him and the fact that,

as Lee put it, people listened to him simply because

he was, after all, a psychiatrist. As Hubert is taken away, the story continues with the editor being so exhausted and worn-out by the visit of the "raving maniac" that he decides to call it a day and head home, where he is greeted by his wife and his daughter, who asks for a bedtime story. The story, which had so far been fast paced and told in conflict dialogue - surely a very loud discussion - ends in a contrastingly peaceful setting as the editor tells his daughter about the events he witnessed at his office, but told in bedtime story mode. |

| This is

Stan Lee's narrative technique to end this little

story with the underlying message that the arguments

of his visitor are so out of touch with the reality

of comic books that they can't be taken seriously -

and as every reader knows, a story which opens with

the set phrase "once upon a time..."

can't be taken as describing factual events. The tone and setting of a fairy tale is further enhanced by the use of a diminuitive as the editor tells his daughter about "an excited little man with nothing more important on his mind". Naturally, this is also a way to portray the Wertham Doppelgänger in a derisive way - which is in fact reminiscent of the full-page editorials Timely/Atlas ran in May 1949:

The text belittled the comic book industry's critic by referring to him as "a Dr Wertham", which at face value was simply hitting back at Wertham with his own rhetoric. On the content level, it also implied - just as the editor's words to his daughter - that this person can not be taken seriously: he is just an angry little man (in a figurative sense, not refering to actual physical height), just a Dr Wertham. Stan Lee had hit back, but chances are that only very few had taken notice at the time, and any reactions would have fallen on barren ground in any case as this was to be the final issue of Suspense. This little piece of Lee narrative thus remains what it was: a highly unconventional story approach for a comic book of its time, and a fairly unqiue artefact of comic book history. Not surprisingly, it was never reprinted until 2005 when Marvel Visionaries: Stan Lee brought the "raving maniac" back to the attention of the community of comic book readers. Stan Lee would, of course, continue as editor at Atlas/Marvel, but he was still some eight years away from his personal moment of glory when he would launch the mighty "Marvel Age of Comics" with Fantastic Four #1 in 1961. Fredric Wertham, however, was just ahead of his most prolific period in his commitment to the anti comic book movement. In November 1953, he would publish an article entitled "What Parents Don't Know" in Ladies' Home Journal, and in May of the next year Reader's Digest would publish "Blueprint to Delinquency" - comic books were, in both cases, the reason to worry about. But most importantly, 1954 would see the publication of the book for which Wertham is most (in)famous - Seduction of the Innocent. He also appeared before the Senate Subcommittee Hearings that same year, and rounded it all off with an article entitled "It's still Murder" in the issue for 9 April 1955 of the Saturday Review of Literature. By that time, Wertham cast a dark shadow over the entire comic book industry, but in that shadow there was also one editor who at least had the consolation of having told Wertham just what kind of person he was and what he thought about his crazy ideas - even if it had just been in a comic book, back in April 1953. But then again, that very same editor would still be around a few years later and, better still, be an important part of nothing short of a revival of the comic book and a new era. When that would happen, in 1961, a certain Dr Wertham would already be out of the spotlight. In the end, Stan Lee won, and Fredric Wertham lost. It was no surprise to anyone who had read Suspense #29. |

BIBLIOGRAPHY |

||

| COVILLE Jamie

(----) "The Comic Book Villain, Dr. Fredric

Wertham M.D.", in Integrative Arts 10:

Seduction of the Innocents and the Attack on Comic

Books, available online and accessed 17 May 2010

at www.psu.edu/dept/inart10_110/inart10/cmbk4cca.html CRIST Judith (1948) "Horror in the Nursery", in Collier's Magazine, 27 March 1948, 22-29 DECKER Dwight (1987) "Fredric Wertham - Anti-Comics Crusader who turned Advocate", originally published in Amazing Heroes (available online and accessed 12 July 2007 at www.art-bin.com/art/awertham.html) GITLIN Marty (2010) Stan Lee: Comic Book Superhero, ABDO Publishing LEE Stan & George Mair (2002) Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee, Fireside MUHLEN Norbert (1949) "Violence in the Comics - Reader's Letters", in Commentary 8 RAPHAEL Jordan & Tom Spurgeon (2003) Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, Chicago Review Press RYAN John (1936) "Are the Comics moral?", in Forum (95/5), 301-304 SCHULTZ H. E. (1949) "Censorship or Self Regulation?", in Journal of Educational Sociology (Vol. 23, #4), 215-224 THRASHER Frederic M. (1949) "The Comics and Delinquency: Cause or Scapegoat", in Journal of Educational Sociology (Vol. 23, #4), 195-205 WERTHAM Fredric (1948) "The Comics - Very funny!", in The Saturday Review of Literature (issue for 29 May), 6-10 WOMACK Michael T. (1992) Fredric Wertham - A Register of his Papers in the Library of Congress, Manuscript, Library of Congress, Washington (availabale online and accessed 26 March 2010 at www.governmentattic.org/2docs/LOC_Wertham-Papers_1992_2007.pdf) WRIGHT Bradford W. (2001) Comic book nation: the transformation of youth culture in America, Johns Hopkins University Press |

||

first poste to the web 15 June

2010 Text is (c) 2010-2014 Adrian Wymann The illustrations presented

here are copyright material. |